Essay: The Structure of the National Government

The first national framework of the United States government, the Articles of Confederation, took effect in 1781 and established only one branch of government. Over the course of the first few years of the new nation, it became clear that this system was not meeting the needs of the people. Under the Articles, Congress was responsible for all the government’s duties – legislative, administrative, and judicial. To meet the needs and expectations of the American people, the United States would require what many Founders termed an “energetic” government. By this they meant a government equipped to protect Americans against internal and external threats; to secure trade and commerce; and to maintain and protect individual rights.

In 1787, fifty-five men gathered in Philadelphia to determine a new national structure of government. This new structure consisted of three branches instead of just one, and diffused power by delegating different responsibilities to each branch. The three branches are described and defined in the first three articles of the Constitution.

Legislative

Article I establishes the legislative branch of the national government – the Congress. Congress is the law-making body of the government, with one chamber composed of the direct representatives of the people and the other chamber composed of representatives of the states. These two chambers, or “houses,” are the House of Representatives and the Senate. Members of the House of Representatives, the larger of the two houses, are elected by the citizens of their states within separate congressional districts. Each state’s number of representatives is based on its population. Madison argued that the size of both houses of Congress should be determined by population. However, the Connecticut Compromise (also known as the “Great Compromise”), a result of a concession made to the delegates representing the smaller states at the Constitutional Convention, mandated equal representation in the upper house of Congress, the Senate. Originally each state’s legislature chose its two U.S. Senators, but in 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment provided for the direct popular election of Senators within each state.

The Framers expected these two houses of Congress to be different in character, with each responsible for different aspects of the legislative function.

Originally conceived as the “people’s house,” the House of Representatives was entrusted with the “power of the purse.” Tax and appropriation legislation must originate in the House. Representatives must be at least 25 years old, have been a United States citizen for at least seven years, and reside in the state from which they are elected. All of the Representatives are eligible for re-election every two years. The House currently has 435 members.

Members of the House of Representatives, the larger of the two houses, are elected by the citizens of their states within separate congressional districts. Each state’s number of representatives is based on its population.

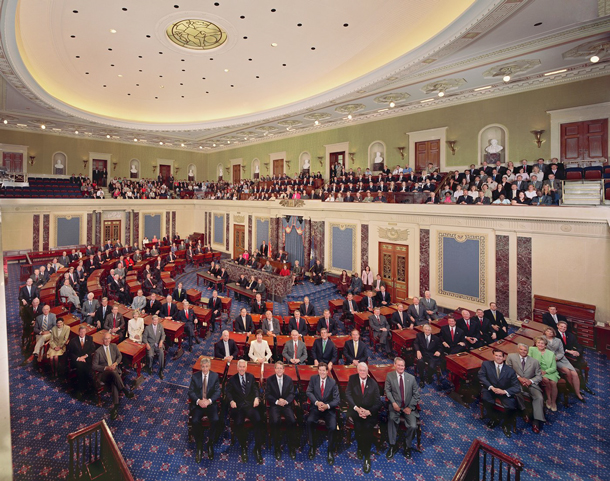

The Senate, on the other hand, was designed to be the more deliberative, slower-moving body of the legislature. Senators must be at least thirty years old, have been a citizen of the United States for at least nine years, and reside in the state from which they are elected. Senators have a six-year term of office, which are staggered so that every two years one-third of Senators are elected. In keeping with its distinctive character, the Senate is the body that ratifies treaties and the president’s nominees for high level offices or federal judicial positions. The Senate also serves as the “court” for trials if the House of Representatives passes articles of impeachment.

The Senate was designed to be the more deliberative, slower-moving body of the legislature.

Executive

The general administration of the government falls to the president and the executive branch. The president is assigned many roles. As chief executive, the president is responsible for ensuring that laws are carried out as written and in accordance with the Constitution. As commander in chief, the president oversees military operations. As head of state, the president is the nation’s representative to the world at large.

The position of responsibility that the executive holds is reflected in the requirements for the office: the president must be at least 35 years old, a natural-born citizen of the United States, and have resided in the U.S. for at least 14 years. The 14-year requirement might seem arbitrary, but it ensured that the first president would have been in the country on the eve of the Revolutionary War and thus fully committed to the new nation.

The residency requirement in the case of both the Congress and the president was meant to protect the fledgling nation from undue influence by other countries.

Over time, the power of the executive branch has greatly expanded. Perhaps the most recognized person in the United States, the president is often the face of the entire nation within the country and around the world. In the twentieth century, many citizens came to expect the federal government to mitigate problems. Today, the American public looks to the president for answers to many pressing issues including healthcare, unemployment, homeland security, and natural disasters. In many respects the executive branch wields more influence and power today than the Framers intended.

One of the president’s constitutionally required responsibilities is to report annually to Congress on the state of the union. Today the president makes a nationally televised address.

While the executive branch is distinct from the legislature, at times their duties and responsibilities overlap. While the president is responsible for administering all of the executive departments, these departments must first be established by acts of Congress. Another of the president’s constitutionally required responsibilities is to report annually to Congress on the state of the union. Today the president makes a nationally televised address. The president may make legislative recommendations to Congress as well. The legislature is expected to check the power of the president. One such check is that of impeachment, whereby Congress can charge an officer of the government – such as the president – with criminal charges. The impeachment process allows the legislature to remove offenders from the government.

Judiciary

Article III of the Constitution establishes the Supreme Court of the United States and also provides for “such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” These courts include federal district courts and courts of appeals. States and municipal governments also may establish their own courts. The purpose of courts is to administer justice and interpret the law. The court system handles criminal cases involving crimes, such as murder or robbery, where one of the parties is the state or national government. It also determines civil cases, in which one individual or group accuses another individual or group of causing a harm or injury.

Higher level courts, such as courts of appeal or the Supreme Court, focus almost exclusively on reviewing the decisions of lower courts and, as they apply to the case, interpreting the meaning of laws.

While the principle of judicial review, or determination by courts of a law’s constitutionality, had already been practiced by some states prior to the ratification of the United States Constitution, the Supreme Court first struck down part of a federal law on constitutional grounds in Marbury v. Madison (1803). Chief Justice John Marshall argued that “an act of the legislature repugnant to the constitution is void.” Despite not being explicitly included in the Constitution, the determination of a law’s constitutionality is now considered one of the most important roles of the Supreme Court and provides an important check on the power of Congress and the president. In recent decades, the Supreme Court has ruled on the constitutionality of a wide variety of laws, dealing with issues such as affirmative action, gay marriage, gun control, and medical marijuana. For example, in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), the Supreme Court ruled that Congress can criminalize the cultivation of marijuana for personal use even in states that have approved the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes.

As a result of the Supreme Court’s application of judicial review and its interpretation of the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, a number of constitutional provisions have been interpreted in ways that have expanded the power of the national government and weakened the federal system. The provisions include the Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18) and the Interstate Commerce Clause. Interpretations of the Interstate Commerce Clause have extended the federal government’s regulation over virtually every part of economic life. The result has been a reduction of the sphere in which the states and individual citizens can manage their affairs.

The Framers of the United States Constitution created a political system based on ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence. They took what they knew of human nature and the history of other governments into account to create a political structure that would protect the rights of individuals and minority interests from government encroachment while still reflecting the will of the people. The Founders assumed a basic level of virtue in the populace and elected officials in order to maintain a successful republic. The Framers thought that the best way to protect the rights of citizens would be through a government energetic enough to do the job but restrained enough to prevent it from trampling the rights it was designed to protect.