Surrender at Appomattox Essay

Adapted from: https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/grant-and-lee-at-appomattox

Option A

Lexile: 990

Word Count: 974

Vocabulary: re-elect, cut-off, tearfully, hand-to-hand, boxcar, sash, obedient, solemnly, malice

The Beginning of the End

In 1864, the Union army started to gain the upper hand against the Confederates. General William T. Sherman captured Atlanta in September and then led his army on its famous “March to the Sea.” Along the way, Sherman’s troops captured Savannah, Georgia, and Columbia, South Carolina, destroying anything useful to the Confederates. At the same time, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had a much larger army than Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant began marching toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

In November, President Abraham Lincoln was re-elected. Soon after, in January 1865, he pushed Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery when it was also ratified by the states later that year in December.

In March, Lincoln gave his Second Inaugural Address, where he urged Americans to heal the nation’s wounds “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” By April 2, Grant broke through the Confederate defenses around Richmond, forcing Lee to retreat west. Union soldiers entered Richmond and raised the American flag while Grant chased after Lee. If Grant could defeat Lee and make him surrender, the war might finally end. But there was still a chance that other Confederate forces would keep fighting. Confederate President Jefferson Davis even encouraged them to start a guerrilla war, which could drag on for years and delay the Union’s victory.

The Confederates are Cut-Off

On April 5, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee led his tired and hungry soldiers across the swollen Appomattox River to a place called Amelia Court House in Virginia. They hoped to find supplies of food waiting for them. But when they arrived, Lee was shocked to learn that the boxcars on the railroad did not have the rations they needed. There was almost no food in the area, and Union soldiers, led by General Philip Sheridan, were getting closer, destroying supply wagons. With no other choice, Lee ordered his men to keep marching west without eating. Some soldiers, still loyal to the cause, obeyed, but more and more began to desert. Lee knew surrender was near.

The next day, April 6, things got worse for the Confederates. Union forces led by General George Custer blocked Lee’s army at Sayler’s Creek. The fighting turned brutal, with hand-to-hand combat, and Lee’s army lost thousands of men. Seeing this, Lee cried, “My God! Has the army been dissolved?” He tried to inspire his troops by riding through their ranks with a battle flag, but it was no use. The army retreated to Farmville, hoping to find food there. However, Union forces were close behind and caught up with them again, forcing the starving soldiers to flee once more.

Surrender Comes

On April 7, Union General Ulysses S. Grant sent a letter to Lee, asking him to surrender to stop more bloodshed. He signed it politely: “Very respectfully, your obedient servant.” Lee replied, saying he did not think his situation was hopeless but wanted to know what terms the Union would offer. Privately, Lee confidently told his officers, “I will strike that man a blow in the morning.” But when one officer suggested surrender, Lee replied, “I trust it has not come to that! We have too many brave men to give up now.”

By April 8, Lee’s army reached the town of Appomattox Court House. They were outnumbered six-to-one, with no hope of reinforcements. Still, Lee planned one last attempt to break through Union lines. On April 9, Palm Sunday, Lee’s plan failed. Union soldiers blocked every escape route. As his generals talked about what to do, one suggested they fight as guerrillas, but Lee refused. “We must think about the country, not just ourselves,” he said. He believed surrender was the honorable choice.

With a heavy heart, Lee wrote to Grant, asking to discuss surrender. Grant, who had been suffering from a migraine, felt great relief when he got the letter. He quickly agreed to meet and sent a respectful reply. They arranged to meet at the home of Wilmer McLean, a man who had moved to Appomattox Court House to escape the war but now saw its final chapter unfold in his living room.

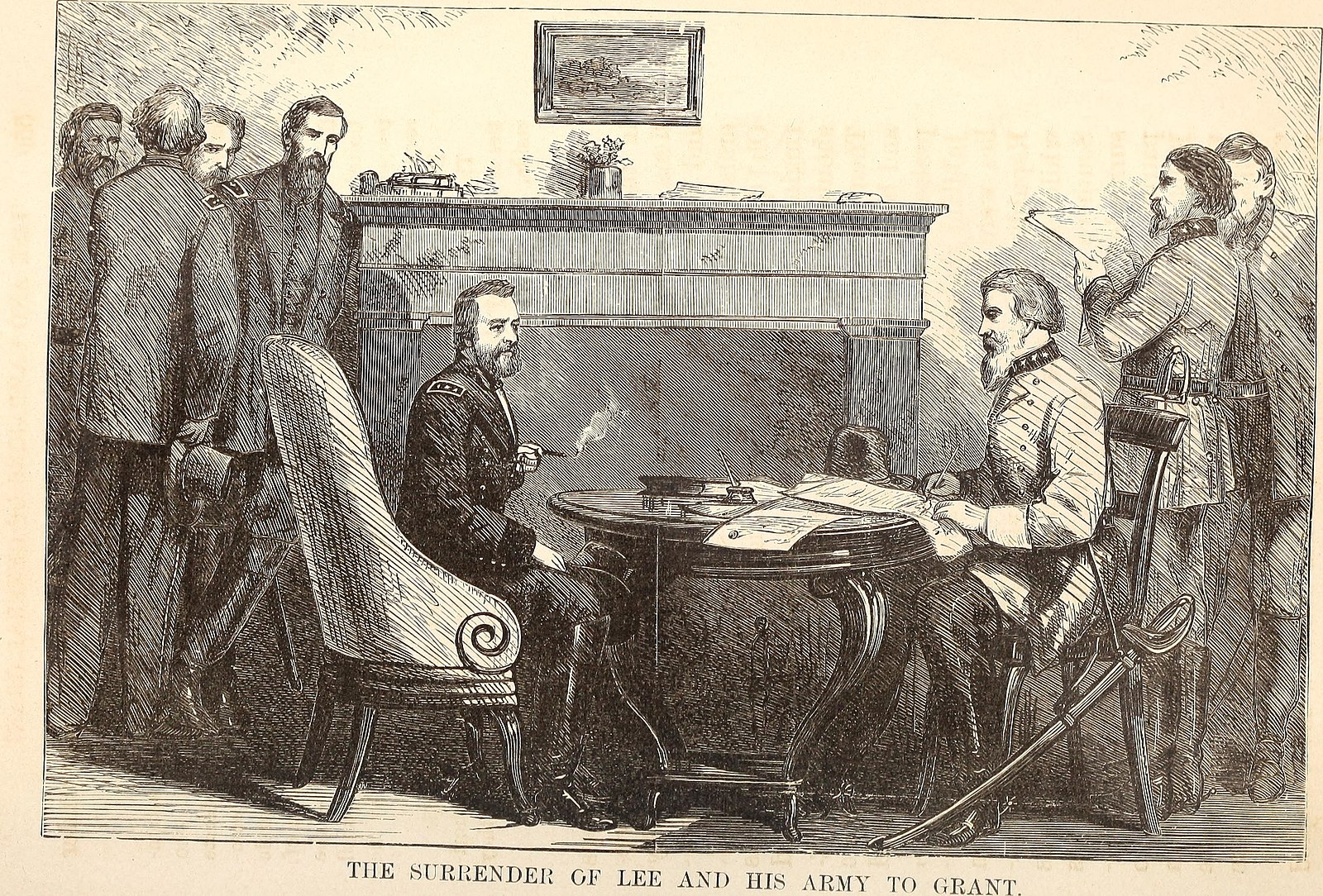

Lee dressed in a clean, elegant uniform, complete with a red sash, shiny boots, and a golden sword. Grant arrived in a simple, muddy uniform. Despite their differences in appearance, both generals treated each other with respect. Grant wrote out the terms of surrender himself and gave them directly to Lee. The Confederate officers could keep their personal weapons, horses, and personal belongings. Lee asked if all his men could keep their horses too, since many were farmers, and Grant agreed. He even offered food for Lee’s starving soldiers. After the formalities, the two men shook hands, and Lee left.

The War Ends

As Lee rode away, Grant stepped onto the porch and lifted his hat in salute. Lee returned the gesture solemnly. Union officers followed Grant’s example, showing respect for their defeated opponents. Grant later explained that he did not want his soldiers to celebrate their enemy’s downfall while they were present. Lee returned to his camp, tearfully telling his men, “I have done the best I could for you. Go home now and be good citizens. I will always be proud of you.”

On April 12, the Confederate troops formally surrendered. Union General Joshua Chamberlain oversaw the ceremony, where Confederate soldiers stacked their weapons in a long, seven-hour parade. As they did, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute their former enemies. Confederate General John Gordon returned the gesture, saluting with his sword. Chamberlain later wrote about the powerful moment, saying it made him want to fall to his knees and pray for forgiveness for everyone. After a war that cost 600,000 lives, Americans on both sides showed remarkable respect for each other in the end.

Option B

Adapted from: https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/grant-and-lee-at-appomattox

Lexile: 950

Word Count: 415

Vocabulary: re-elect, outnumbered, spotless, bloodshed, salute, breakout, gladly, surrender, reinforcement, muddy

The Beginning of the End

In 1864, the Union army began to gain the upper hand. General William T. Sherman captured Atlanta in September and marched to the sea, destroying Confederate supplies and capturing Savannah and Columbia. Meanwhile, Union General Ulysses S. Grant led a larger force toward Richmond, Virginia, facing off against Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

President Abraham Lincoln was re-elected in November and, in January 1865, pushed Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. In March, Lincoln urged national healing in his Second Inaugural Address. On April 2, Grant broke through Richmond’s defenses, and Union troops raised the flag in the Confederate capital. Though Lee retreated, Confederate President Jefferson Davis encouraged continued resistance, even through guerrilla war.

On April 5, Lee’s weary soldiers reached Amelia Court House expecting food, but found none. With Union troops destroying supply lines, Lee had no choice but to keep marching. Many soldiers deserted, or walked away from their job as soldiers. The next day, at Sayler’s Creek, Lee’s army suffered heavy losses in brutal combat. Lee tried to rally his men, but they were forced to retreat again.

On April 7, Grant wrote Lee, requesting his surrender to end the bloodshed. Lee responded, asking for terms but still hoped to fight on. He ultimately rejected surrender, saying, “We have too many brave men to give up now.”

Surrender Comes

By April 8, Lee’s army was surrounded at a town called Appomattox Court House. Outnumbered and without reinforcements, he attempted a final breakout on April 9 but was blocked. Refusing guerrilla warfare, Lee chose to surrender, saying, “We must think about the country, not just ourselves.”

Lee contacted Grant, who gladly accepted. They met in Wilmer McLean’s home, a man who had tried to escape the war by moving there. Lee wore a spotless uniform; Grant arrived in muddy clothes. Despite their differences, they treated each other with respect. Grant allowed Confederate officers to keep personal weapons and offered food to Lee’s starving men. After the meeting, they shook hands and parted with mutual salutes.

The War Ends

On April 12, Confederate troops formally surrendered. General Joshua Chamberlain oversaw the ceremony, ordering his men to salute. Confederate General John Gordon returned the gesture. Chamberlain later wrote the moment moved him deeply, calling for prayer and forgiveness. After a war that claimed 600,000 lives, Americans on both sides showed remarkable respect for each other in the end.

Images:

P. C. Headley, The Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. U. S. Grant, from His Boyhood to the Surrender of Lee (New York: The Derby and Miller Publishing Co., 1866), pg. 594, https://archive.org/details/lifecampaignsofl00head/page/n594.

P. C. Headley, The Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. U. S. Grant, from His Boyhood to the Surrender of Lee (New York: The Derby and Miller Publishing Co., 1866), pg. 594, https://archive.org/details/lifecampaignsofl00head/page/n594.

This 1866 illustration is from a biography that was published shortly after the Civil War. It was written about Ulysses S. Grant and reflects the public admiration for Grant’s military leadership in securing Union victory.