Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Struggle for Women’s Suffrage

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how and why various reform movements developed and expanded from 1800 to 1848

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative focuses on women’s rights and can be used alongside The Women’s Movement and the Seneca Falls Convention Lesson.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, a Second Great Awakening, or religious revival, swept through the United States. The evangelical fervor spawned numerous reform movements such as abolitionism, temperance, and prison reform. Reformers sought to alleviate harsh conditions, work for equality for all, eliminate vice, and create a utopian society. In general, they wanted to achieve a more just society.

In the 1830s and 1840s, these reform movements created organizations that worked to advocate greater equality and improve civil society. They sent out speakers to raise awareness, spread knowledge through pamphlets and newspapers, lobbied politicians at various levels of government, and learned how to create strong organizations. Many of the reform movements were controversial because of the change they sought.

During this time, most Americans accepted the idea that there were different spheres for men and women – men were active in public life through their jobs and politics, and women were responsible for the home. As a result of these gender roles, women suffered inequality in most social and political institutions. They could not vote or serve on juries, and married women generally could not own property. They did not have the same educational or professional opportunities as men. The antebellum reform movements gave women an opportunity to participate in politics and public life because of the inherent moral quality of social reform and because, by the 1830s, women were being seen as defenders of morality in society. When they engaged in movements for equality and justice such as abolition and prison reform, women gained practical experience in organizing a movement.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was one of the pioneers in the fight for women’s rights. Born to an affluent family in upstate New York, the “burned-over district” and center of the Second Great Awakening, she received a classical education, unusual for girls at the time. Her parents were Quakers who taught her their values of human equality and abolitionism. In the spring of 1840, the twenty-five-year-old Stanton boarded the Montreal to sail to London on her honeymoon with her new husband, abolitionist Henry Stanton. They were among forty people from the United States (including eight women) who were traveling across the Atlantic to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London.

The three-week voyage was largely uneventful. Stanton and her husband took advantage of the trip to read abolitionist tracts and discuss ideas associated with antislavery. The couple stayed at the grimy lodging house of an abolitionist in Cheapside, London. Nevertheless, they enjoyed touring around the capital and engaging other abolitionists in conversation.

On Friday, June 12, the meeting of some five hundred abolitionists convened in Freemasons’ Hall. Stanton and the other female delegates bristled when they were seated behind the bar and not on the floor of the convention as official participants. Abolitionist leader Wendell Phillips and other American men boldly protested the unequal treatment of women. Phillips stated that excluding women was akin to excluding black delegates. Another famous abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, who arrived late and refused to participate because of the seating issue, later said, “If women should be excluded from its deliberation, my interest in [the convention] would be about destroyed.” Nevertheless, the English hosts were adamant that the women would not be seated, because of the customs of the country. Stanton had suffered discrimination at the hands of those at the vanguard of abolitionist reform. It was a turning point in her life.

This lithograph by John Alfred Vinter depicts the 1840 Anti-Slavery Society Convention in London. Note that in this image, women are included on the floor of the meeting, which was not Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s experience at the time.

While in London, Stanton struck up a friendship with women’s rights advocate Lucretia Mott. Stanton revered the older Mott and was struck by her oratorical ability when she preached at a London Unitarian church. During a sightseeing walk, the two women agreed to hold a convention and organize a society dedicated to women’s rights. After lingering in London for their honeymoon, the newlyweds sailed home in December with Elizabeth dedicated to a new cause for justice.

Over the next few years, the couple had several children and moved to Boston, where Henry practiced law. Elizabeth’s time was largely consumed by domestic affairs, though she was still very interested in women’s rights. In 1847, she moved her family to New York after her father offered her a piece of property there, with a farmhouse in her own name. The humble town soon became be the site of a historic meeting for women’s rights.

On Sunday, July 9, a half-dozen Quaker women assembled in nearby Waterloo. They met at that time to include Mott, who was visiting from Philadelphia. Mott had encouraged them to also invite Stanton, who made the short ride by train and expressed her discontent at women’s status. The women resolved to call a meeting to “discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.” They placed an ad in the local newspaper and in black abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s North Star announcing the upcoming convention. The following Sunday, Stanton met with a few other women and penned a series of resolutions on her own that she intended to present, and, more importantly, a Declaration of Sentiments based on the Declaration of Independence, after reading that document aloud.

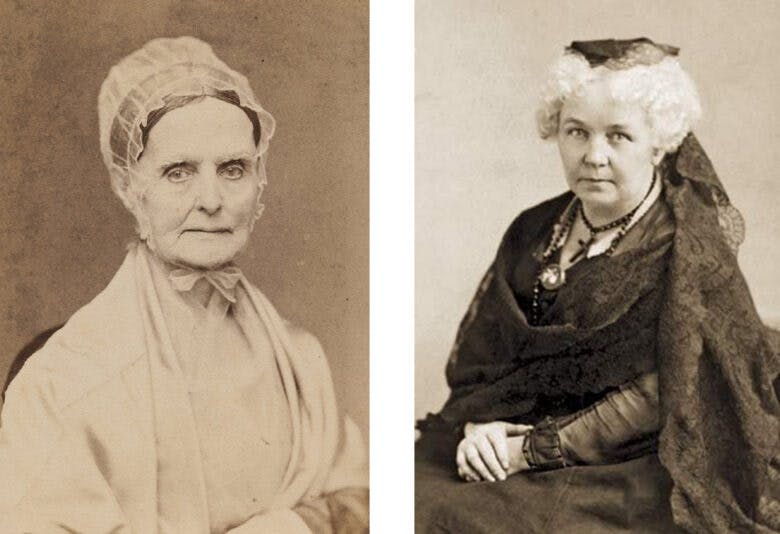

(a) Elizabeth Cady Stanton, shown with two of her sons in an 1848 photograph, and (b) Lucretia Mott in an 1842 oil portrait by Joseph Kyle. Both women emerged from the abolitionist movement as strong advocates of women’s rights.

On Wednesday, July 19, a blistering hot summer day, more than one hundred women assembled for the convention in Seneca Falls’ Wesleyan Chapel. Forty men also appeared and were asked not to speak during the morning session. Stanton delivered an opening address in which she spoke passionately against the subordination and inequality of women. She introduced and read the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments (commonly called the “Declaration of Sentiments”) for attendees’ consideration before adjourning in midafternoon.

The next day was just as hot, but more than three hundred women and men squeezed into the crowded church to consider the Declaration of Sentiments and a series of resolutions. Henry Stanton had warned his wife that if she planned to bring up women’s suffrage, he would stay away. “You will turn the proceedings into a farce,” he told her. Because she definitely would advocate women’s suffrage, he spent the day lecturing in another town.

The assembly heard Stanton read the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments again and noted its familiar words, because it was modeled after the assertion of universal rights in the Declaration of Independence. Stanton’s Declaration featured a significant clarification: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.” Just as the original Declaration had presented a list of grievances against George III, the Declaration of Sentiments included a list of grievances and stated that the “history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman.”

The list included examples of political, civil, economic, and educational inequality. Man had compelled woman to follow laws “in the formation of which she had no voice.” It continued, “He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.” Moreover, “He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.” Men had allowed women “but a subordinate position” in church affairs. Most importantly, and most controversially, the declaration asserted: “It is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise” of the vote.

The Declaration and other resolutions, especially for women’s suffrage, were highly contentious, even at the convention. Mott told Stanton, “Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous.” The other Quaker women, who were not interested in civil affairs, also demurred. Frederick Douglass was the only man to support the resolution and delivered a speech defending women’s right to vote. He said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.” In the end, the resolution barely passed and, as predicted, it was the center of ridicule in the press. That evening, sixty-eight women and thirty-two men signed the convention’s statement.

This souvenir from 1908 was created to commemorate the women and men who signed the Declaration of Sentiments in 1848.

Voting during the new republic had been limited to those with economic independence, because of the republican ideal that only they could be disinterested in exercising the right of suffrage. In New Jersey, the 1776 state constitution allowed all women to vote. Then, in 1790s, the state’s constitution was revised to allow only single women who owned property to vote. This remained in effect until 1807, when suffrage was rescinded due to partisanship disputes. During the 1800s, new ideals of democratic citizenship and suffrage were formed. Stanton led the fight for women’s suffrage on the grounds that the individual right to vote was at the core of citizenship and political participation in the republic. She stated that women’s suffrage was the “stronghold of the fortress” of women’s equality. The long struggle for women’s suffrage thus began with the unflagging fortitude of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her dedication to the cause of justice for women.

Review Questions

1. Upon what document was the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments based as it argued for women’s rights?

- The U.S. Constitution

- The Articles of Confederation

- The Declaration of Independence

- The Declaration of Rights and Grievances

2. Most of the women who led the women’s rights movement in the 1830s and 1840s had gained leadership experience in campaigns for which movement?

- Abolition of slavery

- Separation of church and state

- Democratic socialism

- Equal pay for equal work

3. During the antebellum period women were least likely to have the opportunity to

- receive elementary education

- work outside the home

- vote and run for office

- own property

4. Who did not support adding the right to vote to the 1848 Declaration?

- Frederick Douglass

- Lucretia Mott

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

- Quaker representatives

5. The catalyst for the start of the women’s rights movement was

- the realization that women were excluded from the Constitution

- the exclusion of women as official delegates at the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London

- the strong desire for women to have the right to vote

- the breakdown of traditional roles between men and women

6. Which abolitionist spoke these words in support of the women’s rights movement?

In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Frederick Douglass

- Henry Stanton

- Wendell Phillips

Free Response Questions

- Explain why Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other like-minded individuals supported the movement for women’s rights in the United States.

- Explain the motivation for Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the participants of the Seneca Falls Convention to use the Declaration of Independence as the model for the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments.

AP Practice Questions

“Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.”

The Declaration of Sentiments

Seneca Falls (NY) Convention, July 19-20, 1848

1. The excerpt reflects the sentiments of which group?

- American Indians

- Abolitionists working on behalf of enslaved persons

- Supporters of women’s rights

- Supporters of the rights of Irish and German immigrants

2. Which part of the Bill of Rights do the Declaration’s signers expect to use most frequently?

- The First Amendment

- The Second Amendment

- The Third Amendment

- The Fourth Amendment

3. Which of the following was the most controversial issue in the movement whose sentiments are expressed in the excerpt?

- Equal access to education

- Women’s suffrage

- Explicit support for abolition

- The support for temperance

Primary Sources

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Modern History Sourcebook: Declaration of Sentiments, Seneca Falls Conference, 1848.” https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/senecafalls.asp

Suggested Resources

Ginzberg, Lori D. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life. New York: Hill and Wang, 2009.

Keyssar, Alexander. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Matthews, Jean V. Women’s Struggle for Equality: The First Phase, 1828-1876. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.