Transfer of Presidential Power

by Robert M. S. McDonald

At a time when nearly everywhere regime change occurred as a result of death, murder, war, intrigue, or rebellion, the US Constitution’s 1789 framework for the peaceful transfer of presidential power stood out as truly revolutionary. Even England, which passed along to Americans the most orderly model of executive succession, had witnessed since 1649 the beheading of King Charles I, the forced abdication of Richard Cromwell, and the ouster of James II. There and nearly everywhere else, a successful sovereign was one who served until a natural death. Breaking with the past, Americans devised a system in which the people were sovereign and their election at regular intervals of executive office holders was the norm.

The rules for electing a President laid out by the Constitution’s framers in Article II nonetheless reflected the practices and presumptions of Eighteenth-Century American politics. The Constitution was a creation of states that guarded jealously their ability to act with independence. Each possessed the ability to determine how to select presidential electors equal in number to its two Senators and delegation to the House of Representatives. Because the Founders assumed that electors would frequently favor as candidates individuals from their own states, the Constitution required that each elector cast votes for two individuals eligible for presidency, one of whom must reside in another state. Each state forwarded a tally of its electoral votes to the Senate, which, if no one individual received the majority, referred the election to the House of Representatives. There, Congressmen would vote as members of state delegations, each of which had one vote. The individual to receive support from the majority of state delegations became the President.

This system worked well enough in 1788 and 1792, when electors unanimously selected George Washington to preside over the national government. Although political parties developed during Washington’s administration, he did his best to detach himself from the partisanship of the 1790s and largely succeeded in remaining the sole leader around whom nearly all Americans could unite.

Washington established a tradition of American Chief Executives refusing to stand for election to more than two terms: a practice unchallenged until President Franklin Roosevelt won election to four terms in the 1930s and 1940s but then formalized in 1951 by the Constitution’s Twenty-Second Amendment. It was not only that Washington, by stepping down, avoided inadvertently establishing a precedent for Presidents serving until the ends of their lives (for he would die in 1799) but by removing himself from consideration, he initiated an unbroken string of partisan presidential contests not envisioned by the Constitution’s framers.

The elections of 1796 and 1800 yielded consequences that reflected the new developments in the political landscape. Increasingly organized and nationalized, the Federalist and Republican leadership attempted to make clear to supporters throughout the nation the names of their candidates for both President and Vice President. Federalists supported John Adams and Thomas Pinckney; Republicans supported Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. After a heated campaign, Adams won 71 votes in the Electoral College to Jefferson’s 68. Since any candidate who could gain at least 70 votes became the President, Adams won. But Jefferson—and not Pinckney—came in second, so Adams’s main opponent became his Vice President. Adams’s sole term as President was marked by political strife and diplomatic challenges. Each side believed that the election of 1800 would determine the success or failure of the American experiment, so party discipline increased in that election. This discipline, however, resulted in Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr receiving an equal number of electoral votes. Therefore the election was decided by the Federalist House of Representatives. Only after thirty-five deadlocked ballots did some Federalists change their votes to Jefferson, who took office in 1801.

Jefferson spearheaded a move to ratify the Constitution’s Twelfth Amendment, which provided that electors would cast one vote each for President and Vice President. Enacted in time for the election of 1804, the change not only precluded repetition of a tie between the intended President and Vice President but also reinforced the practice of naming partisan “tickets.”

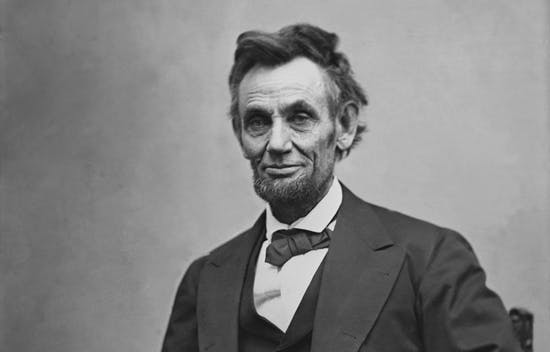

Two national parties dominated American politics until the 1850s, when divisions over issues such as slavery caused these parties to splinter. In 1856, a united Democratic party put forth as its presidential candidate James Buchanan, whose electoral votes—nearly all of which came from southern and Middle Atlantic states—surpassed those of the candidates nominated by the Republican and “Know Nothing” Parties. In 1860 the tables turned. Southerners divided their votes among three candidates while Abraham Lincoln, of the new, northern- based Republican Party, took office with sixty percent of the electoral vote. Yet Lincoln, who was not even on the ballot in ten southern states, received only forty percent of popular vote. Since his party promised to halt the expansion of slavery, southerners feared that they had become a permanent minority. The result was secession—and Civil War. This was the only time in American history that the transfer of power was not peaceful.

The 1860 election constituted the worst, but not the last, instance in which the system established under the Twelfth Amendment failed to yield a result around which nearly all Americans could coalesce. Both the elections of 1876 and 2000, for example, hinged on the electoral votes of states that yielded disputed results.

The final major constitutional innovation relating to the transfer of power deals less with presidential elections, however, and more with presidential succession. While the Twenty Second Amendment limited the number of times an individual could run for the presidency, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment—ratified in 1967 after the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy—clarified procedures when the President died in office, resigned, or was incapacitated. First, the Amendment established definitively that, should the President die or resign, the Vice President would immediately take office as President. Second, it held that a Vice President permanently elevated to the presidency could nominate a new Vice President, who would take office after the approval of the majority of both the House and Senate. Third, the Amendment established a mechanism for the President either to declare himself temporarily incapable of performing his duties or for the Vice President and the majority of the Cabinet to issue such a declaration.

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment was first invoked in 1973 when Gerald Ford replaced Spiro Agnew who had resigned as Nixon’s Vice President. The Amendment served the nation again the following year, when the Watergate scandal prompted Nixon to resign and Ford assumed the presidency. Ford, who became the first President never to have been elected as either President or Vice President, then nominated to serve as Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, whose appointment was confirmed by majorities in both houses of Congress. More recently, the Amendment has been invoked in instances when the Vice President temporarily acted as chief executive while the President underwent medical procedures requiring anesthesia.

In fulfillment of the Founders’ vision, the transfer of executive power within the United States government has been orderly and generally peaceful for more than two centuries. In a world that continues to see regimes toppled by coups, invasions, and armed uprisings, this is no small accomplishment. It owes its success to not only Americans’ fidelity to the rules and procedures laid down in the Constitution but also their willingness to use the amendment process to adapt those rules and procedures to changing times and circumstances.

Dr. Robert M. S. McDonald is Associate Professor of History at the United States Military Academy. A graduate of the University of Virginia and Oxford University, he earned his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is editor of Thomas Jefferson’s Military Academy: Founding West Point. He is completing an edited collection titled Light & Liberty: Thomas Jefferson and the Power of Knowledge as well as a book to be titled Confounding Father: Thomas Jefferson and the Politics of Personality.