The Spanish Flu of 1919

Written by: David Pietrusza, Independent Historian

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes and effects of international and internal migration patterns over time

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative at the beginning of Chapter 11 to explore the Spanish flu’s effect on the United States.

Mercifully, many of the diseases that once plagued humanity, such as polio, tuberculosis, and smallpox, have been brought under better control or even eradicated through innovative science. One disease – influenza or “the flu” – still flares periodically, but in 1918 it really was a plague, a raging pandemic called the Spanish flu that killed tens of millions worldwide in just a few months.

The world had plenty of trouble in 1918. World War I had raged since August 1914. Between nine million and 11 million soldiers died in the conflict, millions more were taken captive, and five million to six million civilians perished. Yet those numbers paled in comparison to the toll of the influenza pandemic. Between 50 and 100 million people died worldwide about 5 percent of the world’s population and the equivalent of more than 400 million based on today’s higher population levels. It was the worst pandemic since the Middle Age’s bubonic plague (“the Black Death”) killed 30 to 60 percent of Europe’s population in the 1300s.

The Spanish flu hit some areas such as the Pacific Islands, Iran, and India far harder than others. More than a quarter of the U.S. population became sick, and at least half a million Americans died in a population of fewer than 100 million. Men, women, and children wore surgical masks on the streets to avoid infection, and movie theaters and vaudeville houses closed. In Canada, the Stanley Cup hockey championship playoff was cancelled. Fear stalked every school, factory, and home.

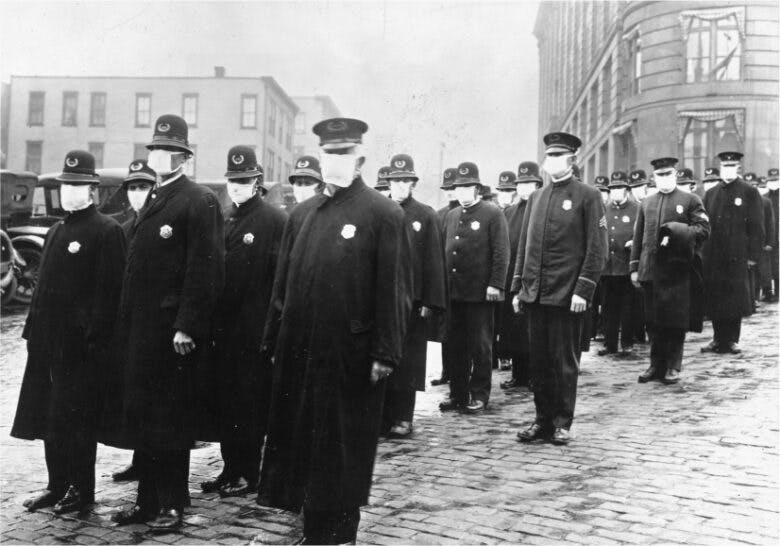

Police officers in Seattle wore face masks provided by the Red Cross to help protect against the flu epidemic of 1918.

In New York, the cities of Rochester and Buffalo closed schools, theaters, pool halls, and saloons. The city of Buffalo went into the coffin business. On October, 10, 1918, Philadelphia was particularly hard hit 528 persons died in a single day. A doctor travelling 12 miles to his home each day reported seeing no people or cars on the road. As author A. A. Hoehling wrote of conditions in that city: “The dead lay sometimes for more than a day besides the gutters, and yet longer in half-abandoned, chill rooming houses. A mixed fear and revulsion had frustrated calls for stretcher-bearers and gravediggers.” An anonymous army doctor at Fort Devens near Boston observed that “it takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were not enough coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce.” Dr. Victor C. Vaughan, former president of the American Medical Association and head of the Army’s Division of Communicable Disease, warned, “If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily have disappeared from the face of the earth within a matter of a few more weeks.”

The strain of flu that raged in 1918 is still known as the Spanish flu for a couple of reasons. First, it infected (but did not kill) the Spanish king, Alfonso XIII – a very high-profile victim. Second, Spain was one of the very few neutral nations in World War I. Wartime censorship was not in force, and developments there, including the spread of flu, could be more freely revealed than where the war raged.

Ordinary flu is painful and weakens people, but it is not usually deadly. The Spanish flu was amazingly harsh. High fevers caused hallucinations. People coughed violently and suffered excruciating pain. They turned black. They bled – not just from the mouth and nose but also from the ears and even, rarely, the eyes. Lungs became so weakened that they crackled when flu victims turned over in their beds. A person could be perfectly healthy in the morning and dead that night.

The worst flu mortality rates usually occur among the very young and the very old, whereas healthy young adults are best able to produce natural antibodies to fight the disease and survive fairly easily. That was not the case in 1918. Very young children did suffer a great deal. In the two years that the Spanish flu raged, the excess deaths for children one to four years of age equaled the normal number of such dead over 20 years. But those 65 years and older suffered an increase of less than 1 percent in excess mortality. Shockingly, more than half the dead were in what was normally the safest group: healthy young adults aged 18 to 45 years. One of the possible reasons is that these flu victims produced far too many antibodies, which overwhelmed not only the flu virus but their own bodies, causing death. If this is true, nature’s “cure” was truly worse than the disease.

Dorothy Deming, a nurse at New York City’s Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, observed that “until the epidemic, death had seemed kindly, coming to the very old, the incurably suffering, or striking suddenly without the knowledge of its victims. Now, we saw death clutch cruelly and ruthlessly at vigorous, well-muscled young women in the prime of Life. Flu dull[s] their resistance, choke[s] their lungs, swamp[s] their hearts. . . . There was nothing but sadness and horror to this senseless waste of human life”.

Nurses at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, DC, demonstrated how to help victims of the Spanish flu. Note the face masks they wear.

The Spanish flu pandemic was not entirely understood at the time. Its origin was unclear, as were the reasons it was so hard to treat and so deadly. Some believed the flu began at the U.S. Army’s huge base at Fort Riley, Kansas. Some said it originated abroad. But wherever it came from, it spread like wildfire. The war only worsened matters, given that soldiers from America, Asia, and Europe, all with different immune systems, had fought side by side in Europe. They lived in close quarters in tents, in barracks, on ships, and in the trenches of France’s western front. They were weakened from the stress of living under fire, and some had lung damage from the poison gas enemy forces lobbed at each other. And, of course, the same ships and trains that carried men and women across the country and around the world in record numbers also transported the microbes that transmitted this deadly strain of disease. In France, the U.S. 88th division counted 444 dead from the flu, but just 90 were killed, wounded, or captured in combat.

“The conditions cannot be visualized by anyone who has not actually seen them,” wrote Colonel E. W. Gibson of Vermont’s 57th Pioneer Division, who witnessed the worsening situation on the troopship Leviathan. “Pools of blood from severe nasal hemorrhages of many patients were scattered throughout the compartments, and the attendants were powerless to escape tracking through the mess, because of the narrow passages between the bunks. The decks became wet and slippery, groans and cries of the terrified added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment, and altogether a true Inferno reign[ed] supreme.”

Wartime censorship complicated the crisis. In 1918, Woodrow Wilson and Congress enacted an amendment to the 1917 Espionage Act (known as the Sedition Act), which decreed that “whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States . . . shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.” This Act made fighting the disease even more difficult because it choked off much honest conversation (and even reporting) about the situation.

As Chicago’s Public Health Commissioner John Dill Robertson stated, “It is our duty to keep the people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic.” Actually, people had good reason for fear. At Chicago’s Cook County Hospital, 40 percent of all influenza patients died.

Eventually, the deadly pandemic ran its course and life returned to normal. A similar pandemic may return to wreak havoc on humanity, particularly with the frequency of international travel. And if it does, censorship will not help the situation any more than it did in 1918.

Review Questions

1. The 1918 Spanish flu outbreak was the worst pandemic since

- smallpox in the nineteenth century

- the bubonic plague in the fourteenth century

- polio in the nineteenth century

- tuberculosis in the eighteenth century

2. As the Spanish flu progressed across the United States, a unique characteristic that emerged was that the disease

- seemed to be without symptoms until the end

- killed a disproportionate number of women

- struck a disproportionate number of people in New England

- killed mostly young, healthy adults

3. A major effect of the Spanish flu on U.S. society was

- the collapse of the economy

- an immediate demand that immigration be halted

- a temporary closure of schools and businesses

- a decline in the medical industry

4. The quote “it is our duty to keep the people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic” from Chicago Public Health Commissioner John Dill Robertson is related to what policy of the U.S. government?

- Wartime censorship of news concerning the Spanish flu

- The need for the medical profession to bring an end to the epidemic

- Encouragement of accurate reporting regarding the epidemic

- Temporary halting of migration

5. The passage of the Sedition Act made it even more difficult to fight the flu pandemic because

- it stifled honest discussion and reporting of the disease

- it allowed the arrest of many of the health-care workers fighting the disease

- it increased immigration and thus the flow of disease carriers into the United States

- it reopened schools and businesses that had been closed to control the contagion

Free Response Questions

- Explain the impact of Spanish influenza on commerce in the United States.

- Analyze the role that censorship of free speech played in the nation’s ability to fight the Spanish flu pandemic.

- Compare society’s response to the Spanish flu pandemic in 1919 with the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. What similarities do you notice?

AP Practice Questions

A 1919 public health broadside provides information on the Spanish flu pandemic.

1. The information presented in the broadside at the provided link could be used to support which of the following conclusions?

- The government developed public policies for fighting the disease.

- Private business banned individuals on the basis of their health status.

- Censorship impeded the spread of information about the disease.

- Widespread panic set in because there was little understanding of the way the disease spread.

2. The publication of this broadside most likely indicates

- an expansion of the role of the federal government

- the widespread health concerns caused by the epidemic

- the national government’s concern about the effects of the epidemic on trade

- the ignorance of most citizens of the time about healthy habits

3. The situation that prompted the broadside can be best described as

- the Red Scare created a fear of socialism in America

- people feared America becoming involved in another European war if the United States joined the League of Nations

- the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan led a fear that personal freedoms would be lost

- a devastating Spanish flu epidemic spread fear, misery, and death around the world

Primary Sources

Price, George M. “Influenza-Destroyer and Teacher: A General Confession by the Public Health Authorities of a Continent.” The Survey 41, no. 12 (1918): 367-369.

“Quarantine and Isolation in Influenza.” Journal of the American Medical Association 71, no. 15 (1918): 1220.

“Spanish Influenza the Way to Treat It and to Avoid It.” A Vicks VapoRub advertisement. Portland Morning Oregonian. January 8, 1919, p. 6. https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83025138/1919-01-08/ed-1/seq-6/

Suggested Resources

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza. New York: Viking, 2004.

Hoehling, A. A. The Great Epidemic. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1961.

Iezzoni, Lynette. Influenza 1918: The Worst Epidemic in American History. New York: TV Books, 1999.

Kolata, Gina. Flu: The Story of The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Tucker, Spencer and Priscilla Mary Roberts (eds.). World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006.

Withington, John. Disaster!: A History of Earthquakes, Floods, Plagues, and Other Catastrophes. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2010.