The Hartford Convention

Written by: Jeremy D. Bailey, University of Houston

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes and effects of policy debates in the early republic

Suggested Sequencing

This Decision Point can be assigned with The Missouri Compromise Decision Point and the Was the Election of 1800 a Revolution? Point-Counterpoint to provide students introduction into the issue of sectionalism.

In December 1814, twenty-six New England Federalists from Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, and New Hampshire assembled in a convention in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss their opposition to James Madison’s administration and, in particular, to the ongoing war with England. Most immediately, the War of 1812 had been terrible for the New England economy, but before the war, New England had already borne the brunt of Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807 and its later iteration as the Non-Intercourse Act. More than that, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 had doubled the size of the United States, and, as everyone could see, future expansion would be southern and western. This meant the new states in that region would likely be agricultural, so they would probably elect representatives who identified more with Jeffersonian Republicans than with New England Federalists.

Finally, the Twelfth Amendment, ratified in 1804, streamlined the process for electing the president, making it less likely that the House would have to settle contested elections, as it had done in 1800. As Federalists at the time argued, the Twelfth Amendment thus made it more likely that the Jeffersonian majority would be able to dominate presidential elections in the foreseeable future. To make matters worse, in the fall of 1814, Madison let it be known that he would seek a national draft.

When the Federalist delegates assembled that winter in Hartford, they met in secret and kept no record of their deliberations. They were divided about how to meet the challenges before them. During the blockade, New Englanders had frustrated Jefferson’s policy by finding ways to guide British ships to port and evade U.S. ships that were enforcing the law. Now, in wartime, those activities continued. Moreover, Federalist governors had resisted Madison’s call for the state militias to aid the War Department. The governor of Massachusetts went so far as to secretly negotiate with Great Britain, offering England a part of Maine in order to end the war. Leading newspapers throughout the region advocated resistance to taxes and even secession. Gouverneur Morris, who, at the Federal Convention of 1787, had written the final draft of the Constitution, now argued that freedom was more important than Union and advocated the creation of a New England Confederacy that would be able to repeal the debt acquired during the war because the Federalists opposed it. Timothy Pickering, who had represented Massachusetts in Congress and had served as both secretary of State and secretary of War under George Washington, also flirted with the idea of secession as a way to renegotiate a Union more favorable to New England interests. Going back to 1804, Pickering had imagined a separate country in the North, connecting New York, New England, and parts of Canada.

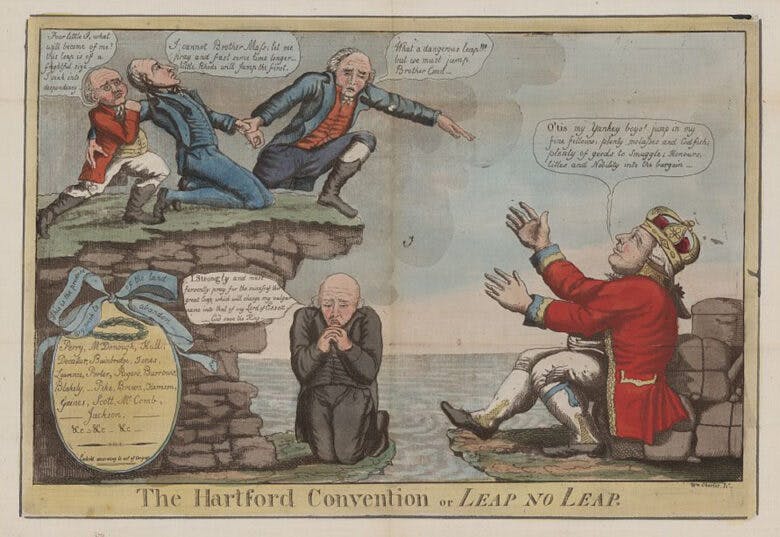

In this political cartoon depicting the Hartford Convention, New England states, represented by the four men, are pondering whether to leap off the cliff (symbolic of treason). The British monarch is holding out his hands and encouraging them by offering bribes. Massachusetts is pressing two of the men, Rhode Island and Connecticut, to jump with him while the fourth prays for the success of their endeavor.

Others, however, rejected the idea of secession and preferred a more moderate course, arguing that staying in the Union better served New England’s interests. They advocated issuing a protest, and for some the model was the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, written by Madison and Jefferson in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions did not mention secession, but arguably they laid the intellectual groundwork for later theories of secession by asserting a “compact theory” of the Union, holding that the states were the original parties to the federal compact. As such, they held the power to judge the constitutionality of federal legislation. To the writers of the earlier resolutions, the Alien Acts and the Sedition Act had been clearly unconstitutional, and accordingly the resolutions requested that other states join them to protest those acts. In his Kentucky Resolution, Jefferson had gone as far as to claim that a state could nullify laws it believed to be unconstitutional. Madison’s version, however, used the word “interpose” instead of nullify.

The more moderate Federalists at the 1814 Hartford Convention won the debate. Under the leadership of Harrison Gray Otis, the Convention became a venue for expressing grievances about the war and the trade embargo, instead of declaring secession. The Convention’s final report did reflect on the idea of secession as a remedy to the “multiplied abuses of bad administrations,” but it eventually recommended against it, citing George Washington’s Farewell Address as “conclusive” in its recommendation of national harmony. To the extent that it followed the model of Virginia and Kentucky, the report was producing a message of protest, not declaring a doctrine of interposition. Furthermore, the report included a declaration of grievances along with a list of proposed amendments to the Constitution.

A wealthy business owner and politician from Boston, Harrison Gray Otis, shown in an 1833 portrait, was one of the leading Federalists of his time.

These proposed amendments were meant to make New England more competitive in national electoral politics and restore what the Hartford delegates believed was the “balance of power which existed among the original states.” The Convention proposed abolishing the representation of three-fifths of the enslaved persons in slave states, creating a supermajority requirement for Congress to add new states to the Union, and excluding naturalized citizens from federal office. The Convention also proposed amendments that would limit the power of the national government, for example by creating a supermajority requirement for wars that were not defensive and by placing a limit on Congress’s power to issue embargoes. Finally, the Hartford delegates proposed softening the power of the president by instituting a one-term limit and creating a geographic balance in terms of presidents. Thinking of the lock Virginia seemed to enjoy on the presidency, they wanted to forbid the election of presidents from the same state in two successive terms.

The product of the Hartford Convention, then, did not come close to being a statement of secession or a declaration of New England independence. Like the Declaration of Independence, it included a list of grievances, but it recommended addressing these grievances by amending the Constitution rather than scrapping it. The Convention was a victory for the moderates and a defeat for the more militant Federalists, who had undoubtedly pursued secession in their deliberations. It was also a dead end, because none of the recommended amendments had any chance of being constitutionally proposed and ratified. Arguably, however, although the motivation was partly secessionist, the final result was a victory for the constitutional process.

Even if the outcome was more moderate than it might have been, the implied threat of secession did not serve the Hartford Federalists well in the electoral arena. Even if secession had been thwarted by the leadership of the moderates, the secretive nature of the Convention, and the alliance it revealed among New England’s state legislatures, raised the possibility of secession, which did not serve the Federalists well in the electoral arena. Most of all, the Convention coincided with Andrew Jackson’s tremendous victory over the British at New Orleans and then with the news of the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war itself. The prospect of peace took the wind out of antiwar sails, and Jackson’s victory made New England’s questioning of the war seem disloyal. Indeed, for a generation, the Hartford Convention was synonymous with treason in the minds of opponents. James Monroe, another Virginian, won the presidency in 1816, while the Federalists won only three states—Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware. In 1820, Monroe ran unopposed, which suggested the country had moved beyond the contest between the Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian parties and entered a new era, the Era of Good Feelings. Or, more precisely, Monroe’s victory suggested that the contest between Hamilton and Jefferson was over. The party of Jefferson had won the electoral battle, though the Jeffersonian Republicans instituted many of Hamilton’s ideas in the next decade, such as chartering the Second National Bank.

Finally, President Madison did not respond to the resistance in New England generally, or to the Hartford Convention in particular, by curtailing freedom of speech or suspending habeas corpus. Although some historians fault Madison for his handling of the war effort, others have pointed out that he is somewhat unusual for not undermining civil liberties during wartime, as did the controversial actions of presidents John Adams, Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt.

Review Questions

1. The amendments proposed by the Hartford Convention included provisions to

- limit New England’s ability to win electoral victories

- limit the power of Congress to declare war

- increase the power of Congress to admit new states into the Union

- apply the Three-Fifths Compromise to all the states in the Union

2. Democratic-Republicans in the early nineteenth century supported all the following except

- the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory

- the recommendations of the Hartford Convention

- passage of the Embargo and Non-Intercourse Acts

- U.S. entry into the War of 1812

3. In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, New Englanders more and more considered themselves a political minority because of

- geographic expansion of the south and west

- the decline of the tobacco industry

- expansion of world trade

- increased immigration from Ireland and Germany

4. How did the Federalists attempt to resist Democratic Republican rule in the early nineteenth century?

- They blocked the creation of new states by setting impossibly high population requirements.

- They declared the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional.

- Some advocated secession, while moderates proposed a series of amendments to increase New England’s political power.

- They voted for U.S. entry into the War of 1812 to increase New England’s shipbuilding capacity.

5. The “compact theory” of government most clearly means

- states have the right to secede

- states hold the power to judge the constitutionality of federal legislation

- federal law supersedes state law

- the national government lacks the authority to increase the size of the United States

6. The Hartford Convention’s recommendations and the Declaration of Independence are similar because they both

- called for violent secession from the ruling government

- called for amending the U.S. Constitution

- laid the primary blame for the conflict on the king of England

- included a list of grievances against the ruling government

7. As a result of the Hartford Convention and its aftermath, the Federalist Party became

- the politically dominant party in New England and the Old Northwest Territory

- a formidable opponent of the rising Jacksonian Democrats

- a signal that Hamiltonian forces dominated the national government

- a political party with diminishing electoral support

Free Response Questions

- The increasing hostilities between France and Great Britain in the lead-up to the War of 1812 affected the regions of the United States differently. Explain these impacts.

- Explain why some in New England believed the region should secede from the United States.

- Explain the similarities and differences between the Hartford Convention and the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions.

AP Practice Questions

“The power of compelling the militia and other citizens of the United States, by a forcible draft or conscription to serve in the regular armies, as proposed in a late official letter of the Secretary of War, is not delegated to Congress by the Constitution, and the exercise of it would be not less dangerous to their liberties, than hostile to the sovereignty of the States. The effort to deduce this power from the right of raising armies, is a flagrant attempt to pervert the sense of the clause in the Constitution which confers that right, and is incompatible with other provisions in that instrument. The armies of the United States have always been raised by contract, never by conscription, and nothing more can be wanting to a Government, possessing the power thus claimed, to enable it to usurp the entire control of the militia, in derogation of the authority of the State, and to convert it by impressment into a standing army.”

Report and Resolutions of the Hartford Convention, 1815

Refer to the excerpt provided.

1. The delegates who signed the resolution believed

- the United States government was acting within its constitutional authority

- the national government should use its authority to create a standing army

- a federal draft law was “necessary and proper,” according to the Constitution

- constitutional power supported the state governments in this situation

2. Which group would most strongly support the argument?

- Southern planters

- Congressmen from newly admitted western states

- New England state legislators

- Small farmers from the mid-Atlantic states

Primary Sources

“Reports and Resolutions of the Hartford Convention.” https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Report_and_Resolutions_of_the_Hartford_Convention

Suggested Resources

Bailey Jeremy D. Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Banner, James M. Jr. To the Hartford Convention: The Federalists and the Origins of Party Politics in Massachusetts, 1789-1815. New York: Knopf, 1970.

Wood, Gordon. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.