Remember the Maine! Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the effects of the Spanish-American War

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with The Philippine-American War Narrative and the Redfield Proctor vs. Mark Twain on American Imperialism, 1898-1906 Primary Source to explore the U.S. role in overseas conflicts.

In late January 1898, President William McKinley dispatched the U.S.S. Maine to Cuban waters to protect American citizens and business investments during ongoing tensions between Spain and its colony, Cuba. A Cuban revolutionary movement against imperialist Spain had started in 1895, and Spain had responded by mercilessly suppressing the insurgency. General Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed “the butcher,” was sent by Spain to force thousands of Cubans into relocation camps and burn crops to deny the countryside to the rebels. Many Americans increasingly wanted to aid the Cuban rebels and prevent European tyranny in what they saw as the nation’s backyard. William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, and other newspaper moguls publicized the atrocities committed by Spain’s military and encouraged sympathy for the Cuban people. Hearst told one of his photographers, “You furnish the pictures. I’ll furnish the war.”

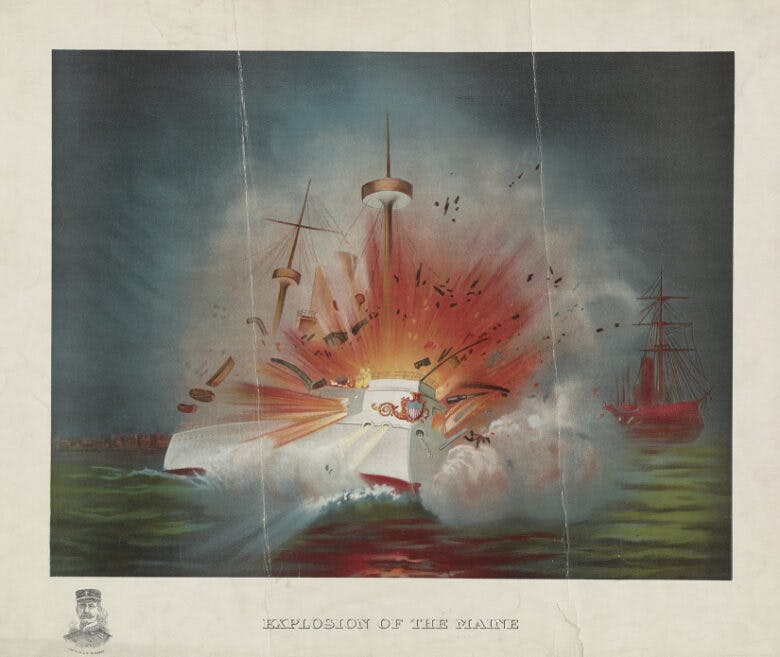

During the evening of February 15, Cubans celebrated the pre-Lenten holiday of carnival while the U.S.S. Maine floated quietly in Havana harbor. At 9:40 p.m., a powerful explosion rocked the ship, killing 260 sailors and marines aboard and throwing flames and smoke hundreds of feet into the air. Although the explosion was later ruled an accident, the American press blamed Spain and called for war with a sensationalist style of reporting called “yellow journalism.” Hearst reported the news with an offer to pay a $50,000 reward for capture of the “perpetrator of the Maine outrage.” The public clamored for war with the popular cry, “Remember the Maine!”

This 1898 chromolithograph depicts the Maine‘s deadly explosion in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898.

President McKinley and Congress had sought alternatives to war for years and continued working for a diplomatic solution even after the sinking of the Maine. However, assistant secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt repositioned naval warships close to Cuba and sent Commodore George Dewey to attack the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in the Philippines when his boss, secretary of the Navy John Long, was out of town. Dewey attacked on May 1 and sank the entire Spanish fleet in the Philippines. Roosevelt thought McKinley had “no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.” Hearst printed an inflammatory private letter from the Spanish ambassador to the United States, Don Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, that called McKinley “weak.”

Public pressure mounted on President McKinley to seek a declaration of war. On April 11, he asked Congress to declare war on Spain and invoked Spanish atrocities, the memory of the Maine, and the Monroe Doctrine as justification. A week later, Congress passed the Teller amendment disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba. Congress declared war on April 25, the same day Roosevelt received approval to raise his cavalry regiment, nicknamed the “Rough Riders.”

Theodore Roosevelt had been born to a wealthy New York family and raised in privilege. He attended Harvard University and dedicated his life to public service and writing books. He served as a member of the New York Assembly, worked on the U.S. Civil Service Commission, and was the New York City Police Commissioner. He wrote The Naval War of 1812 and a series of books called The Winning of the West. He was an admirer of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, which tied national greatness to a strong navy and maritime trade.

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, pictured here in October 1898 in his Rough Riders uniform, which was designed to make the cavalry unit look more like cowboys.

Roosevelt felt it was his patriotic duty to serve his country. “It does not seem to me that it would be honorable for a man who has consistently advocated a warlike policy not to be willing himself to bear the brunt of carrying out that policy.” Moreover, Roosevelt praised “the soldierly virtues” to demonstrate virility of individual men and the nation, which he believed had gone soft with the affluence and decadence of the Gilded Age. He sought to test himself in battle and win glory.

Roosevelt hopped on a train and headed to Texas to join the new First Volunteer Cavalry regiment of roughneck westerners including cowboys, hunters, wilderness scouts, and American Indians. Ivy League athletes who also sought to serve patriotically and test themselves joined the regiment. Commander Roosevelt felt comfortable in both worlds because he had attended Harvard but also owned a ranch in North Dakota. His regiment trained in the dusty heat of San Antonio, in the shadow of the Alamo, under him and Congressional Medal of Honor winner Colonel Leonard Wood. The men were known as the Rough Riders.

The regiment loaded their horses in June and boarded trains for a four-day trip to Tampa, Florida, which served as the embarkation point for troops departing to Cuba. On June 22, the Rough Riders and thousands of American troops landed unopposed at Daiquirí on the coast of Cuba. Though many were without their horses, they gathered up their packs and started marching toward the main Spanish army at the capital of Santiago.

The Rough Riders were unprepared for the tropical heat and forbidding jungle terrain they encountered during the difficult march. On June 24, the U.S. Army was slowly advancing when hidden Spanish troops waiting to ambush opened fire from their hidden thickets and the U.S. lines became chaotic. The Americans were unable to see the Spanish troops because they used smokeless gunpowder. Colonel Wood restored order, and the Americans finally spotted the enemy and returned fire. The Spanish withdrew to their fortified positions on the hills in front of Santiago. The Americans continued marching along the road to Santiago for a week, persisting through the humidity, swarms of insects, and tropical rain of the jungle. By June 30, they had made it to the base of Kettle Hill, where the Spanish were entrenched and had their guns sighted on the surrounding plains.

The American artillery was brought forward first and fired at the enemy entrenched on Kettle Hill. The Spanish heavy guns answered, ripping into the waiting American lines with hot shrapnel that cut down several Rough Riders and men from other units, including many Cuban allies. Roosevelt himself was wounded in the arm but ignored the pain. He and the entire army grew impatient as they awaited orders to attack.

When the order finally came, a mounted Roosevelt led from the front wearing a conspicuous sombrero with a blue polka-dot handkerchief, an inviting target for Spanish sharpshooters and an inspiration for his men. They forded a small river and halted at a sunken lane for protection. The Rough Riders were flanked on either side by the African American “Buffalo Soldiers” of the regular Ninth and Tenth cavalry regiments, commanded by white officer John “Black Jack” Pershing. The American troops charged up the incline yelling and firing their weapons. Roosevelt had dismounted and led the charge on foot. He was one of the first Americans up the hill as the Spanish poured withering fire into the American and Cuban ranks, killing and wounding several dozen men before being driven off. When the Spaniards atop adjacent San Juan Hill fired on the Rough Riders, Roosevelt marched his men down Kettle Hill and prepared to take San Juan Hill.

This 1898 photograph shows Colonel Roosevelt (center, in glasses) and his men atop San Juan Hill, Cuba, after the battle.

Roosevelt called his men to follow him into battle but apparently few heard. Thinking they accompanied him, however, he “jumped over the wire fence in front of us and started at the double.” Running into battle with bullets whizzing into the grass all around him, Roosevelt noticed only four men had joined him, and one was quickly mortally wounded. Angry, Roosevelt ran back to his troops and rallied them. Finally, all heard his orders as he jumped over the fence again and led the charge, supported by the heavy fire of Gatling guns. Once again, the Rough Riders and other regiments successfully drove the Spaniards off the hill and cheered loudly. The Americans dug into their positions for the night and collapsed, exhausted after a day of strenuous fighting.

After a week, the Americans had repulsed Spanish counterattacks and taken Santiago relatively easily. The Spanish capitulated and sued for peace by mid-July.

Roosevelt was immediately celebrated as a national war hero, and his reputation benefitted from his writing a series of articles and then a book, Rough Riders, describing his experience. A painting, “The Charge of the Rough Riders,” by his friend Frederic Remington, helped to cement his status. Roosevelt rode his fame to high office, first being elected governor of New York and then becoming vice president under McKinley before assuming the presidency when McKinley was assassinated in 1901. Roosevelt believed he was denied the Medal of Honor he desperately wanted because he angered the Army after publicly criticizing it when some of his men perished from tropical diseases, food poisoning, and poor medical care in Cuba after the end of the fighting. Nevertheless, he later stated, “San Juan was the great day in my life.” The contributions of African American soldiers went largely unrecognized; the Rough Riders won most of the fame during this era of Jim Crow segregation.

Under President Roosevelt, the United States issued the Platt Amendment in 1901, claiming a right to intervene in Cuban affairs and control its treaty-making ability. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904 asserted that the United States could intervene in Latin American affairs to prevent a European presence. The United States also built the Panama Canal during Roosevelt’s administration, to establish a two-ocean navy in the Atlantic and Pacific.

The Spanish-American War was a turning point in history because the nation then assumed global responsibilities for a growing empire that included Cuba, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The Filipinos, led by Emilio Aguinaldo, rebelled against the American control just as they had against the Spanish. The insurrection resulted in the loss of thousands of American and Filipino lives. The Spanish-American War that was fought in Cuba and the Philippines sparked a sharp debate between imperialists and anti-imperialists in the United States over the course of American foreign policy and global power, a debate that continued into the next century.

This 1898 political cartoon depicts the tension in the Philippines between the United States (represented by Uncle Sam) and Spain, which owned the territory.

Review Questions

1.

New York Journal reads “Who Destroyed the Maine? $50,000 reward. Destruction of the war ship Maine was the work of an enemy. Assistant Secretary Roosevelt convinced the explosion of the war ship was not an accident. The journal offers $50,000 reward for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their death. Naval officers unanimous that the ship was destroyed on purpose.” Printed twice on the page is the advertisement: “$50,000! $50,000 Reward! For the detection of the perpetrator of the Maine Outrage!””>

The headline best exemplifies

- yellow journalism

- isolationist sentiment

- pro-Spanish sympathies

- rejection of the Monroe Doctrine

2. During his time as assistant secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt’s position on American intervention in Cuba agreed least with that of

- the Cuban people

- the American public

- publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer

- President William McKinley

3. At the outset of the Spanish-American War, Congress passed the Teller Amendment, which

- declared Cuba to be an American territory

- stated the United States would not annex Cuba

- allowed the United States to appoint Cuba’s governor and legislature

- linked the government of the Philippines with that of Cuba

4. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History influenced figures like Theodore Roosevelt to

- question Great Britain’s reliance on naval power

- reject plans for an interoceanic canal

- support increased spending for naval forces

- limit American influence to the Caribbean

5. Immediately after the Spanish-American War, Theodore Roosevelt’s popularity was enhanced by his

- command of an African American unit

- receipt of the Congressional Medal of Honor

- valiant but failed attempt to secure San Juan Hill

- depiction in a painting by artist Frederick Remington

6. Extended American intervention in Cuba was justified by all the following except

- the Monroe Doctrine

- the Teller Amendment

- the Platt Amendment

- the Roosevelt Corollary

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the media contributed to an American declaration of war against Spain in 1898.

- Explain how America’s place in the world changed with the conclusion of the Spanish-American War.

AP Practice Questions

From the 1904 book American Boy’s Life of Theodore Roosevelt

1. The events depicted in this image most directly led to

- rejection of American interventionism in Latin America

- an end to peacetime conscription

- intense debate about America’s proper role in the world

- rejection of the Progressive Era at the polls

2. A historian might use this image to support the point that

- innovations in communication and technology contributed to a growth of mass culture

- war fatigue led to a reevaluation of American foreign policy

- political instability led to pressure to reform the American political system

- the American military suffered from inadequate funding

3. This image was created in response to

- the end of the Plains Wars with the American Indians

- America’s victory in the Spanish-American War

- America’s entry into World War I

- the U.S. annexation of the Philippines

Primary Sources

Roosevelt, Theodore. The Rough Riders. New York: Da Capo, 1990.

Suggested Resources

Brands, H.W.TR: The Last Romantic. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. New York: Knopf, 2002.

Gardner, Mark Lee. Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill. New York: William Morrow, 2016.

Morris, Edmund. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Ballantine, 1979.

Thomas, Evan. The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898. New York: Back Bay Books, 2010.

Van Atta, John R. Charging Up San Juan Hill: Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of Imperial America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.