Montezuma and Cortés

Written by: Mark Christensen, Assumption College

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes of exploration and conquest of the New World by various European nations

- Explain how and why European and Native American perspectives of others developed and changed in the period

Suggested Sequencing

This should be used following the First Contacts Narrative and the Cortés’ Account of Tenochtitlan, 1522 Primary Source.

The ninth ruler of the Aztec Empire, Montezuma, was not overly concerned by the report he had just received. For the past few years, his spies had been informing him of the activities of the Spanish and their expeditions. Now, in 1519, a report came to him of another group of foreign men coming from the Yucatan Peninsula and entering the eastern borders of his central Mexican empire. Montezuma resided at a distance from the coast in the capital city of Tenochtitlan, which is today Mexico City. A strong ruler who had aggressively expanded the Aztec Empire to its height, Montezuma weighed his options concerning this new expedition before deciding whether to welcome its leader, Hernando Cortés.

Montezuma led an empire that served its patron deity through the capture and sacrifice of war captives. He was no stranger to warfare and certainly was not intimidated by Cortés and his Spanish companions. Like other Native Americans, Montezuma viewed the bearded white Spaniards with curiosity, yet he understood that they were just as mortal as he was, and certainly not gods. That said, he faced not only Cortés and his few hundred Spaniards but also thousands of Spain’s Native American allies, many from Montezuma’s unbeatable military rival and neighbor, Tlaxcala. Montezuma thus knew the Spaniards could successfully defend themselves in battle. Not only did their steel swords hold a decisive advantage over the obsidian axes and clubs used by the Native Americans of central Mexico but the Spaniards could also garner support from towns at odds with the Aztecs, which might supply them with food and warriors.

Like many empires, the Aztec culture conquered its neighbors with military might and forced them to pay tribute in labor and goods. Even the capital, Tenochtitlan, was held together by political and military persuasion, which allowed tensions to simmer under the surface. For example, although the city of Tlatelolco was incorporated into Tenochtitlan as a sister city in the fifteenth century, it had been at odds with Tenochtitlan and its rulers long before the Spaniards arrived (its inhabitants later blamed Montezuma for the Aztecs’ defeat). Such division provided Cortés with a ready supply of allies willing to throw off the yoke of Aztec oppression.

Montezuma also considered his duty to his people. When faced with the decision of what to do about Cortés, he could jump headfirst into war, certainly. But a lengthy war could affect the planting and harvesting season, which would mean famine for his subjects. So he chose a more pragmatic approach: Montezuma would welcome and entertain the foreigner, impress him with the greatness of the vast capital city, and persuade him to be an ally. If all else failed, Montezuma always had the option of war. For the sake of his people and empire, however, a negotiation with Cortés made much more sense.

Montezuma’s decision to welcome Cortés into his city reflected his strength and intelligence, not his weakness. Years of reports of Spaniards along the coastline suggested they were in the Americas to stay. Even defeating Cortés outright would only delay the inevitable negotiations that must be made with the newcomers. Montezuma rightly concluded that it was better to negotiate with the Spaniards on his terms, in his city, from a position of strength. After all, Cortés had already shown himself willing to ally with other Native American cities. Surely Montezuma could convince him that he would be the most valuable ally of all and negotiate a deal that would allow him to keep his empire intact and his people safe.

Thus Montezuma welcomed and entertained the Spaniards for a few months. He showed them his temples, the enormous markets where goods from all over his empire were sold, his zoo, and his palaces. Montezuma did not think Cortés was the reincarnation of an ancient Aztec deity, as some thought at the time. He was just a powerful rival who could be bent to Montezuma’s will and interests.

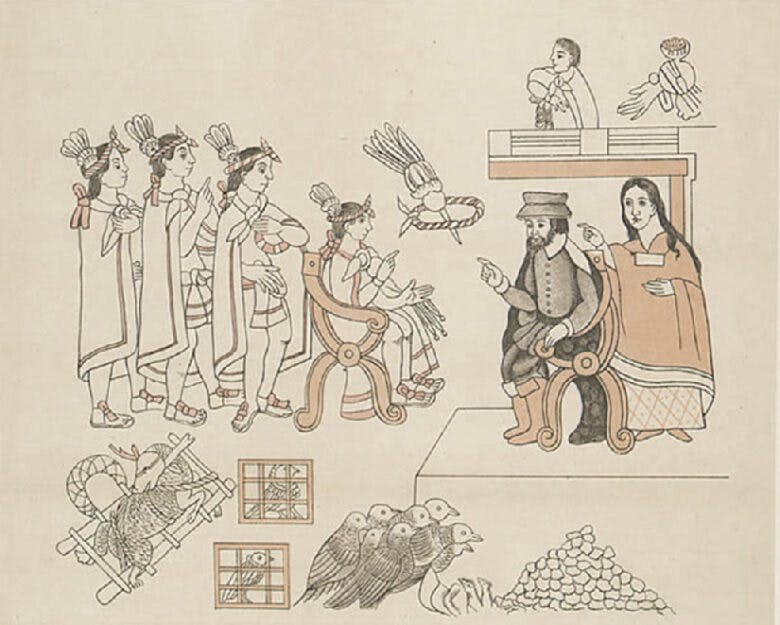

The meeting of Cortés and Montezuma is shown in this image from a Tlaxcalan mural. The mural was completed by 1560, nearly 40 years after the Spanish conquest. Cortés’ interpreter, a Native American woman known as Malinche or Doña Marina, stands behind him.

Some Native Americans from Tlateloloco later encouraged the belief that omens predicting the destruction of his empire, including an eclipse, a comet, and a terrible storm, had frightened Montezuma. Yet this was an attempt to show Montezuma as a weak, indecisive, and superstitious leader who was to blame for the fall of Tenochtitlan. Instead, he was strong and decisive, and he knew what he wanted from the Spanish.

Images such as this one, in which Montezuma watches a large comet streak across the sky, perpetuated the belief that Montezuma’s superstition was to blame for the fall of the Aztec empire.

For his part, during his stay in Tenochtitlan, Cortés took every opportunity to search for precious metals and convert Montezuma to Christianity. Montezuma also informed Cortés of his people’s worldview and deities, their traditions, and customs. As a good host, he tolerated some of Cortés’s requests and even offered one of his daughters to Cortés as a potential wife, in the time-honored fashion of Aztecs building alliances. Yet with his emphasis on precious metals and his foreign religion, Cortés began to wear out his welcome.

Then news from Montezuma’s spies changed everything. In April 1520, they reported that approximately 800 Spaniards had arrived on the coast with 13 ships. Cortés knew at once that the hostile fleet, led by Panfilo de Narvaez, had certainly come from his disgruntled patron, Diego de Velázquez. Cortés had betrayed de Velázquez by embarking on this expedition without permission—an act of insubordination for which he could be imprisoned. With a Spanish fleet approaching, however, Montezuma saw his chance to get rid of his increasingly bothersome guest and prepared his people for war. His decision to welcome Cortés had paid off—Montezuma had learned all he could of the interlopers and their intentions and now decided to act.

Aware of his precarious situation, Cortés moved first by imprisoning Montezuma; the exact details of this event are sparse and contradictory. Leaving a group of men behind to guard the Aztec emperor, Cortés left for the coast in May 1520 to deal with the newcomers. He defeated the Spanish force, the remnants of which decided to join him. In his absence, however, his men had massacred a group of Native Americans gathered to celebrate a religious festival. Relations between the two cultures had reached their low point, and when Cortés returned a month later, the Aztecs began their assault. Desperate and fighting for their lives, the Spaniards fled the city after suffering massive casualties (as did their Native American allies), but they killed Montezuma before they left.

Montezuma’s decision to allow Cortés to enter his city cost him his life and ended his empire. It was reasonable for him to assume that the potential benefit of an alliance with the Spaniards was worth the risk, but in the end it was a misjudgment. Montezuma failed to achieve the outcome he desired, because his empire was overwhelmed by a technologically superior foe bent on conquest and wealth.

Review Questions

1. Native American allies helped the Spanish defeat the Aztecs because

- the Spanish conquered them first and demanded it

- they saw it as an opportunity to rid themselves of Aztec oppression

- they believed the Spanish to be gods and therefore wanted to please them

- they believed aiding the Spanish would rid them of smallpox

2. Which of the following best describes the context for the political situation in the Aztec capital prior to Cortés’s arrival?

- Tenochtitlan was experiencing a Golden Age.

- Tenochtitlan was recovering from a recent defeat by the Aztecs’ rivals, the Tlaxcalans.

- Tenochtitlan was held together by political and military might, and tensions simmered below the surface.

- Tenochtitlan’s elite had begun the process of converting to Christianity thanks to missionaries who preceded Cortés’s men.

3. Ultimately, Montezuma invited Cortés into Tenochtitlan because

- Montezuma felt it better to negotiate on his terms rather than risk outright war

- Cortés forced his way through the city walls and Montezuma had no choice

- Montezuma interpreted a comet as an omen indicating he should meet with the Spanish

- Montezuma reasoned that refusing to meet with the Spanish would lead to an outbreak of disease

4. What modern city stands where the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan once was?

- Machu Picchu

- Cuzco

- Lima

- Mexico City

5. Groups seeking to discredit the idea that Montezuma made a rational decision to invite the Spanish into Tenochtitlan would use which of the following to support their argument?

- Montezuma believed the Spanish to be gods.

- Montezuma felt it would be best to meet the Spanish in his own city.

- Montezuma believed he could convince the Spanish to become his allies.

- Montezuma wanted to avoid outright war before gaining additional information about Spanish intentions.

6. What event contributed to the defeat of the Aztecs?

- The arrival of a Spanish fleet

- A massive earthquake, which rivals took an as omen to join the Spanish forces

- Cortés’s refusal to wed one of Montezuma’s daughters

- Cortés’s repeated emphasis on searching for precious metals and promoting Catholicism

Free Response Questions

- Analyze the extent to which the major motives of European exploration were reflected in the story of Cortés and Montezuma.

- What factors enabled the Spanish to conquer the Aztec Empire? Explain your answer.

AP Practice Questions

“‘I know full well of all that has happened to you from Puntunchan to here, and I also know how those of Cempoal and Tascalteca have told you much evil of me; believe only what you see with your eyes, for those are my enemies, and some were my vassals, and have rebelled against me at your coming and said those things to gain favor with you. I also know that they have told you the walls of my houses are, made of gold, and that the floor mats in my rooms and other things in my household are likewise of gold, and that I was, and claimed to be, a god; and many other things besides. The houses as you see are of stone and lime and clay.’

Then he raised his clothes and showed me his body, saying, as he grasped his arms and trunk with his hands, ‘See that I am of flesh and blood like you and all other men, and I am mortal and substantial. See how they have lied to you?’”

Montezuma’s Greeting to Hernán Cortés

“Cortés asked him: ‘Are you Motecuhzoma? Are you the king? Is it true that you are the king Motecuhzoma?’

And the king said: ‘Yes, I am Motecuhzoma.’ Then he stood up to welcome Cortés; he came forward, bowed his head low and addressed him in these words: “Our lord, you are weary. The journey has tired you, but now you have arrived on the earth. You have come to your city, Mexico. You have come here to sit on your throne, to sit under its canopy.

‘The kings who have gone before, your representatives, guarded it and preserved it for your coming. . . .

If only they are watching! If only they can see what I see!’

‘No, it is not a dream. I am not walking in my sleep. I am not seeing you in my dreams. . . . I have seen you at last. . . .And now you have come out of the clouds and mists to sit on your throne again.’

‘This was foretold by the kings who governed your city, and now it has taken place. You have come back to us; you have come down from the sky. Rest now, and take possession of your royal houses. Welcome to your land, my lords!’”

An Aztec account written after the conquest

Refer to the excerpts provided.1. According to the first excerpt, which of the following motivated conquistadors like Cortés to explore and conquer lands in the New World?

- The desire to have friendly relations with the Native Americans

- The desire to gain wealth

- The desire to gain allies against Muslim invaders from the Ottoman Empire

- The desire to conquer Asia and Africa

2. The second excerpt best supports which of the following conclusions?

- Montezuma felt it would be best to meet Cortés in his own city on his own terms.

- Montezuma believed he could convince the Spanish to become allies with him.

- Montezuma wanted to avoid outright war before gaining additional information about Spanish intentions.

- Montezuma believed the Spanish to be gods.

3. Which group would mostly likely support the point of view of the second excerpt?

- Cortés and his officers

- Aztec nobles

- Aztec enemies from Cempoal and Tascalteca

- Spanish missionaries

Primary Sources

Cortés, Hernán. “Modern History Sourcebook: Hernán Cortés: from Second Letter to Charles V, 1520.” In The Library of Original Sources, Vol. V: 9th to 16th Centuries, edited by Oliver J. Thatcher, 317–326. Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1520cortes.asp

LeonPortilla, Miguel. “Modern History Sourcebook: An Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico.” https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/aztecs1.asp

Pagden, Anthony, trans. “Moctezuma’s Greeting to Hernan Cortes.” http://web.archive.org/web/20000304002237/ http://www.humanities.ccny.cuny.edu:80/history/reader/cortez.htm

Suggested Resources

Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin’s Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.