Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks

Written by: Stephen Puleo, Independent Historian

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how regional differences related to slavery caused tension in the years leading up to the Civil War

- Explain the political causes of the Civil War

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative to further illustrate the tension between northern and southern states, culminating in the start of the Civil War.

Gold-headed cane in hand, South Carolina representative Preston Brooks approached an unsuspecting Senator Charles Sumner on Thursday, May 22, 1856, thankful the wait was finally over. The two days since Charles Sumner’s inflammatory speech on the Senate floor had seemed like a lifetime. Even moments earlier, Brooks had delayed his actions when he noticed a woman in the Senate Chamber; he could hardly carry out his mission to avenge his kin and his region in the presence of a woman. It would violate the code of honor by which he lived as a southern gentleman.

When the woman finished her conversation and left, Brooks waited another moment, his eyes boring into the abolitionist Sumner, whom Brooks viewed as one of the most dangerous threats to the future of the South. Sumner, from Massachusetts, seemed oblivious to his presence and to anything else except the speech copies he was signing, or “franking,” for constituents, the same speech he had delivered over five hours between May 19 and 20 and that had infuriated Brooks in the first place.

In the oration, which he titled “The Crime Against Kansas,” Sumner had vilified southern slaveholders for violence occurring in Kansas, insulted Brooks’s home state, and hurled personal slurs against Brooks’s second cousin, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler.

Brooks felt a “high and holy obligation” to avenge the insults Sumner had directed toward his family and his state. Anything less and he would be humiliated as a man, a slaveholder, a proud South Carolinian, an advocate for the southern way of life. Brooks saw no alternative; his years of adhering to the southern code of honor demanded he retaliate against Sumner. However, by beating Sumner rather than challenging him to a duel, Brooks was implying that his opponent was not a gentleman worthy of respect.

Brooks reached Sumner’s desk, where the Senator was writing, head down, unaware of his presence. Sumner’s chair was drawn up close, his long legs pinned under the desk.

“Mr. Sumner,” Brooks began. “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” And then he raised his cane.

Two essential components of Charles Sumner’s character had guided his preparation for and delivery of the controversial speech – one easily defined and virtuous, the other complex and dark. Without question, Sumner’s antislavery convictions were admirable and resolute. He never wavered in denouncing slavery’s evils, demanding that it be wiped out of existence. By 1856, the abolition of slavery, pure and simple, was the driving force of his political life. In this quest, he stood taller and firmer than anyone in America, including Abraham Lincoln and William Lloyd Garrison. Yet Sumner’s dark side was every bit as influential in shaping his persona. Egotism and narcissism also consumed him; his arrogance was well known to friend and foe alike. He cared little for the opinions or feelings of others, and his voice dripped with condescension when he delivered advice. He was intolerant of criticism, nearly incapable of conciliation, and virtually humorless; he had few close friends and only lukewarm political alliances. In short, the inspirational music of Sumner’s antislavery message was often drowned out by the tone-deaf insolence of the messenger.

In his bold, confrontational, even incendiary speech, Sumner did not stop with a recitation of issues and possible resolutions. Instead, he viciously insulted the elderly Andrew Butler, who was not present in the Chamber (he was at home recovering from a stroke) and the state from which Butler hailed. He charged that Butler had “chosen a mistress [who] . . . though ugly to others is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight – I mean the harlot, Slavery.” He taunted Butler for his state’s reliance on “the shameful imbecility of slavery.” When he had finished, northerners and southerners objected strongly to Sumner’s personal invective, especially because Butler was not present to defend himself.

Preston Brooks simmered. In the 36 hours following the speech, whether he visited a “parlor, or drawing room, or dinner party,” the talk was all about Sumner’s insults to Brooks’s “State and his countrymen” and what could be done in response. “I felt it to be my duty to relieve Butler and avenge the insult to my State,” he said.

When Sumner looked up and saw Brooks raise his arm, he moved as if to rise, but Brooks struck him on the top of the head with the smaller end of the cane, causing an outpouring of blood that blinded Sumner.

Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner’s 1856 speech condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act and argued that Kansas should be immediately admitted as a free state.

Brooks then struck Sumner again and again on his head and face with the heavy end of the cane. Sumner struggled to rise, but his legs were still pinned under his desk. After a dozen blows to the head, his eyes blinded with blood, he roared and made a desperate effort to rise. His trapped legs wrenched the desk (which was bolted to the floor by an iron plate and heavy screws) from its moorings. Sumner staggered forward down the aisle, now an even easier target for Brooks, who continued to beat him across the head. Brooks rained down blows upon Sumner. “Every lick went where I intended,” Brooks recalled later.

As he pounded Sumner, Brooks’s cane snapped, but he continued to strike the senator with the splintered piece. “Oh, Lord,” Sumner gasped, “Oh! Oh!” Brooks grabbed the helpless and reeling Sumner by the lapel and held him up with one hand while continuing to strike him with the other. He thrashed Sumner, delivering “about 30 first-rate stripes.” Near the end of the beating, Sumner was “entirely insensible,” though before he succumbed, he “bellowed like a calf,” according to Brooks.

Two New York representatives, bystanders in the Senate Chamber, finally intervened as the fracas wound down. One cradled the fallen Sumner, who, head and face covered in blood, groaned piteously at first and then went silent, “as senseless as a corpse for several minutes, his head bleeding copiously. . . and blood saturating his clothes.” Friends led Brooks to a side room. Other southerners picked up pieces of the splintered cane; later, these scraps were fashioned into rings that many southern lawmakers wore on neck chains as a sign of solidarity with Brooks.

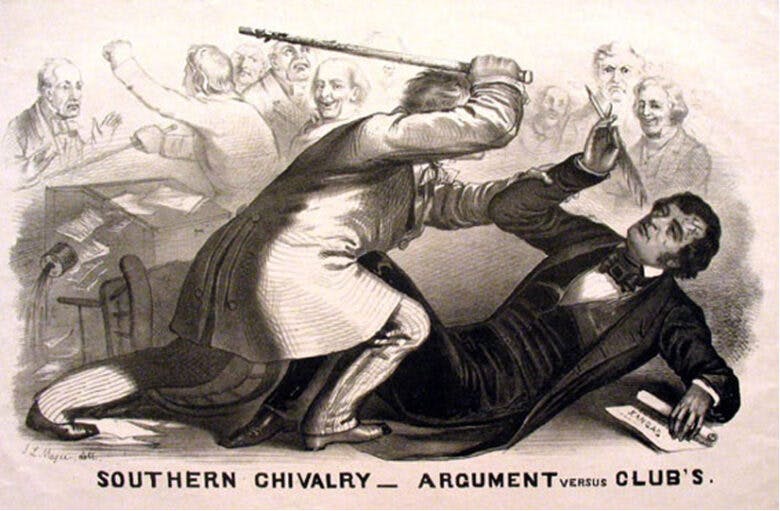

This famous 1856 political cartoon of the caning of Charles Sumner criticizes Preston Brooks for using a club against Sumner’s penned argument.

This famous 1856 political cartoon of the caning of Charles Sumner criticizes Preston Brooks for using a club against Sumner’s penned argument.Meanwhile, colleagues helped a wobbly Sumner into a carriage and accompanied him to his nearby lodgings, where he was examined by a doctor. Shocked and in pain, the Senator remarked before falling asleep, “I could not believe such a thing like this was possible.”

News of the caning swept the country like a brushfire. Most of the nation’s 3,000 newspapers carried the story on their front pages; in the South, Brooks was celebrated with glorious editorials about southern honor and pride. In the North, he was vilified as a brute and a barbarian who perhaps represented the bulk of slaveholders. Hundreds of southerners sent him replica canes as gifts, many inscribed with the words “Hit him again!” Northerners – even moderates who normally would have thought Sumner too radical on the slavery issue – found themselves supporting the Massachusetts senator unequivocally.

Brooks not only shattered his cane during the beating, he also destroyed any pretense of civility between North and South. One of the most shocking and provocative events in American. history, the caning convinced both sides that the gulf between them was unbridgeable. Its violence fueled the sectionalism of the decade. Moderate voices now were drowned out; extremist views became intractable and locked both sides in a collision course. Sumner survived the beating – although he was absent for more than three years while recovering – but political compromise suffered a mortal blow. Slavery was now seen as part of a titanic moral struggle between sections with very different characters.

The caning was part of the dramatic rush of events toward war, which included the increasing militancy of abolitionists, the “Bleeding Kansas” event, the rise of the antislavery Republican Party, the Dred Scott decision of 1857, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the election of Abraham Lincoln, and the secession of southern states. It shocked and divided the country and helped push America to armed conflict between regions. Several factors, predominately slavery, conspired to cause the Civil War, and the caning was inextricably linked to them.

Review Questions

1. The “crime against Kansas” that Senator Charles Sumner referred to in his congressional speech was the

- South’s ultimate responsibility for the violence resulting from the Kansas-Nebraska Act

- pro-union riots that occurred in support of organized labor

- decision to create up to five slave states from the Kansas-Nebraska Territory

- refusal of Congress to allow popular sovereignty to proceed in Kansas

2. In the antebellum South, the southern code of honor demanded

- gender equality

- mediation to resolve disputes

- the avenging of insults

- political compromise on the issue of slavery

3. On the question of slavery, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner’s view was most similar to that of

- President James Buchanan

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Senator Stephen Douglas

- Senator Henry Clay

4. In the aftermath of the Sumner-Brooks incident, it became apparent that

- Henry Clay’s efforts to seek a political solution to slavery would work

- Congressional representatives from west of the Mississippi River would earn the 1860 presidential nominations

- opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act was diminishing

- political compromise between the North and the South was unlikely

5. Which statement is most accurate regarding the Sumner-Brooks incident?

- Both men were considered heroes in their respective regions, further increasing sectional tensions.

- Charles Sumner retired from office and later became a supporter of lenient treatment of the South during Reconstruction.

- The Supreme Court censured Preston Brooks and removed him from Congress.

- Preston Brooks was jailed for assault, but his apology served to lessen sectional discord.

6. What event immediately preceded the Sumner-Brooks incident?

- The Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision.

- “Bleeding Kansas”

- Compromise of 1850

- Presidential election of Abraham Lincoln

Free Response Questions

- Explain Preston Brooks’s response to Charles Sumner’s “Crime Against Kansas” speech in the Senate.

- Explain how the Sumner-Brooks incident affected the slavery debate.

AP Practice Questions

Arguments of the Chivalry, 1856. About a week after the violent event depicted in the image, Henry Ward Beecher gave a speech in New York in which he proclaimed, “The symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon.”

Arguments of the Chivalry, 1856. About a week after the violent event depicted in the image, Henry Ward Beecher gave a speech in New York in which he proclaimed, “The symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon.”1. Which of the following contradicts the statement, “The symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon,” in the cartoon?

- Publication of the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- Passage of laws in northern states refusing to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act

- John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry

- Issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation

2. The image most directly resulted from

- the question of whether to declare war on Mexico

- the admission of California as a free state

- the secession of South Carolina

- the sectional tension regarding slavery in the United States

3. The provided illustration reflects a growing belief that

- the legislation Henry Clay promoted in 1820 and 1850 achieved political stability

- political compromise was unlikely to succeed

- third parties could not win electoral votes

- northern writers produced work of little literary value

Primary Sources

Select Committee appointed to inquire upon the circumstances attending the assault committed upon the person of Hon. Charles Sumner, a member of the Senate, H.R. Rep. 182-34, (1856).

https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/SumnerInvestigation1856.pdf

Brooks, Preston S. The Preston S. Brooks Papers. South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

Lucas, Gloria Ramsey, Slave Records of Edgefield, South Carolina. Edgefield, SC: Edgefield Historical Society, 2010.

The Resolutions of the Legislature of Massachusetts Relative to the Recent Assault upon the Hon. Mr. Sumner. June 11, 1856.

Palmer, Beverly Wilson, ed. The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner, 2 vols. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990.

Sumner, Charles. The Papers of Charles Sumner, 1811-1874. Boston Public Library..

Sumner, Charles. The Works of Charles Sumner. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875.

Suggested Resources

Dietrich, Ken. “Ever Able, Manly, Just and Heroic: Preston Smith Brooks and the Myth of Southern Manhood.” Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association(2011):27-38.

Donald, David Herbert. Charles Sumer and the Coming of the Civil War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Freeman, Joanne B. The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018.

Gienapp, William E. “The Crime Against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party.” Civil War History. September (1979):218-245.

Hoffer, Williamjames Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Mathis, Robert Neil. “Preston Smith Brooks: The Man and His Image.” South Carolina Historical Magazine. October (1978):296-310.

Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union, Volume 1:Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847-1852; Ordeal of the Union, Volume 2:A House Dividing, 1852-1857. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1947.

Puleo, Stephen. The Caning: The Assault that Drove America to Civil War. New York: Westholme, 2011.

Slusser, Daniel Lawrence. “In Defense of Southern Honor: Preston Brooks and the Attack on Charles Sumner.”CalPoly Journal of History, 2 (2010):98-110.