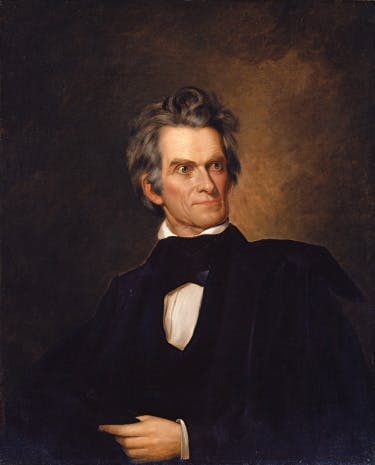

John C. Calhoun, “Slavery as a Positive Good,” 1837

Use this primary source text to explore key historical events.

Suggested Sequencing

- This Primary Source should be accompanied by the Is the Concurrent Majority Theory Faithful to the Ideals of the Constitution? Point-Counterpoint and the John C. Calhoun, South Carolina Exposition and Protest, 1828 Primary Source to highlight Calhoun’s impact on domestic politics during the Age of Jackson.

Introduction

As abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison grew louder in their attacks on slavery and southern culture, several white southerners produced a new defense of slavery. This defense was not only a response to the growing abolitionist movement but also to Nat Turner’s Rebellion (which terrified southern whites) and the expansion of the lucrative cotton economy into the Deep South. In this speech, John C. Calhoun, then a U.S. senator, vigorously defended the institution of slavery and stated the essence of this new intellectual defense of the institution: Southerners must stop apologizing for slavery and reject the idea that it was a necessary evil. Instead, Calhoun insisted, slavery was a “positive good.” He went further, making legal arguments about the Constitution protecting states’ rights to preserve slavery. Calhoun then offered a moral defense of slavery by claiming it to be a more humane method of organizing labor than the conditions wage laborers faced in industrial cities in Europe and the northern United States.

Sourcing Questions

- Why did white southerners provide a new defense of slavery in the 1830s?

- What central arguments did Calhoun use to frame his defense of slavery?

| Vocabulary | Text |

|---|---|

| encroachment (n): gradual intrusion over someone else’s property, rights, space, and so forth | I do not belong . . . to the school which holds that aggression is to be met by concession. Mine is the opposite creed, which teaches that encroachments must be met at the beginning, and that those who act on the opposite principle are prepared to become slaves. In this case, in particular I hold concession or compromise to be fatal. If we concede an inch, concession would follow concession–compromise would follow compromise, until our ranks would be so broken that effectual resistance would be impossible. We must meet the enemy on the frontier, with a fixed determination of maintaining our position at every hazard. . . . |

| The subject is beyond the jurisdiction of Congress—they have no right to touch it in any shape or form, or to make it the subject of deliberation or discussion. . . . | |

| incendiary (adj): designed to cause fire or, in this context, a deadly conflict | As widely as this incendiary spirit has spread, it has not yet infected this body, or the great mass of the intelligent and business portion of the North; but unless it be speedily stopped, it will spread and work upwards till it brings the two great sections of the Union into deadly conflict. . . . |

| Force Bill: legislation passed by Congress in 1833 during the Nullification Crisis that, among other things, allowed the president to deploy the army to South Carolina to force compliance with the law bayonet (n): a blade that can be fixed to a rifle |

. . . I then predicted that the doctrine of the proclamation and the Force Bill—that this Government had a right, in the last resort, to determine the extent of its own powers, and enforce its decision at the point of the bayonet . . . would at no distant day arouse the dormant spirit of abolitionism. I told him that the doctrine was tantamount to the assumption of unlimited power on the part of the Government, and that such would be the impression on the public mind in a large portion of the Union. |

| The consequence would be inevitable. A large portion of the Northern States believed slavery to be a sin, and would consider it as an obligation of conscience to abolish it if they should feel themselves in any degree responsible for its continuance. . . . I then predicted that it would commence as it has with this fanatical portion of society, and that they would begin their operations on the ignorant, the weak, the young, and the thoughtless –and gradually extend upwards till they would become strong enough to obtain political control . . . | |

| . . . By the necessary course of events, if left to themselves, we must become, finally, two people. It is impossible under the deadly hatred which must spring up between the two great nations, if the present causes are permitted to operate unchecked, that we should continue under the same political system. The conflicting elements would burst the Union asunder, powerful as are the links which hold it together. Abolition and the Union cannot coexist. As the friend of the Union I openly proclaim it–and the sooner it is known the better. . . . We of the South will not, cannot, surrender our institutions. To maintain the existing relations between the two races, inhabiting that section of the Union, is indispensable to the peace and happiness of both. It cannot be subverted without drenching the country in blood . . . | |

| . . . Be it good or bad, [slavery] has grown up with our society and institutions, and is so interwoven with them that to destroy it would be to destroy us as a people. But let me not be understood as admitting, even by implication, that the existing relations between the two races in the slaveholding States is an evil:–far otherwise; I hold it to be a good, as it has thus far proved itself to be to both, and will continue to prove so if not disturbed by the fell spirit of abolition. | |

| I appeal to facts. Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually. | |

| In the meantime, the white or European race, has not degenerated. It has kept pace with its brethren in other sections of the Union where slavery does not exist. It is odious to make comparison; but I appeal to all sides whether the South is not equal in virtue, intelligence, patriotism, courage, disinterestedness, and all the high qualities which adorn our nature. . . . | |

| . . . I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good. . . I hold then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other. . . . | |

| I might well challenge a comparison between them and the more direct, simple, and patriarchal mode by which the labor of the African race is, among us, commanded by the European. I may say with truth, that in few countries so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little exacted from him, or where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age. | |

| Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse. . . . | |

| There is and always has been in an advanced stage of wealth and civilization, a conflict between labor and capital. The condition of society in the South exempts us from the disorders and dangers resulting from this conflict; and which explains why it is that the political condition of the slaveholding States has been so much more stable and quiet than that of the North. |

Comprehension Questions

- Who is the “we” Calhoun refers to?

- What tone does Calhoun set here for the argument that will follow?

- How does Calhoun interpret Congress’s authority on the question of slavery?

- How does Calhoun view the consequences of the Force Bill?

- To whom is Calhoun referring with the phrase “fanatical portion of society”? According to Calhoun, what influence will these fanatics have?

- What does Calhoun see as the inevitable end of a spreading spirit of abolitionism in the United States?

- What argument does Calhoun cite to support his assertion that slavery has been a “good” for African Americans?

- What does Calhoun argue to be economically inevitable in a wealthy, civilized society?

- How does Calhoun characterize the working and living conditions of American enslaved persons?

- How does Calhoun use European wage laborers as support for his assertions about American slaves?

- From what dangerous conflict does the slave system insulate the South, according to Calhoun?

Historical Reasoning Questions

- In what ways does Calhoun use legal arguments to defend the idea that Congress cannot interfere in the institution of slavery?

- How does Calhoun go beyond the traditional legal defenses of slavery and attempt to convince the audience that slavery is, indeed, good for all involved?

Full Text: “Slavery a Positive Good” http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/slavery-a-positive-good/