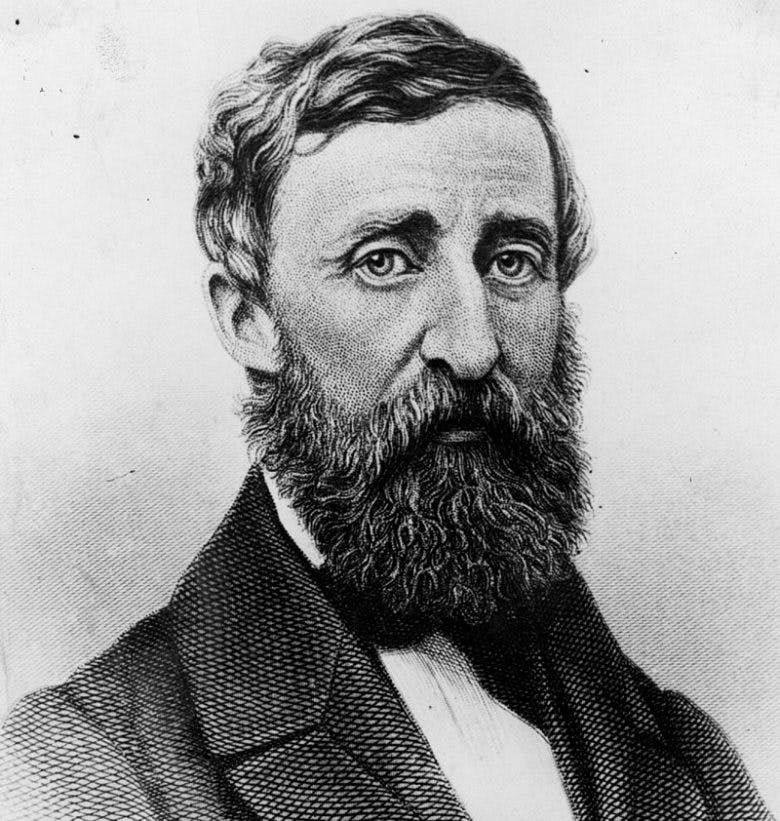

Henry David Thoreau, “Slavery in Massachusetts,” 1854

Use this primary source text to explore key historical events.

Suggested Sequencing

- Use this Primary Source activity with the Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, 1855 Primary Source to develop a better understanding of transcendentalism and the issues that were of concern to transcendentalists in the mid-nineteenth century.

Introduction

After escaping from slavery in Richmond, Anthony Burns stowed away on a ship to Boston, where he attempted to start a new life as an employee at a clothing store. However, Burns’s freedom was short-lived because his owner, Charles Suttle, learned of his location and demanded his return under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Although Burns’s lawyers did their best to prove that the law was unconstitutional, Judge Edward Greely Loring ruled that Burns was to be returned to his owner. On July 4, 1854, about a month after Loring had issued his verdict, the transcendentalist author Henry David Thoreau delivered a powerful speech to a crowd of abolitionists in Framingham, Massachusetts. In the weeks that followed, Thoreau converted his speech into an essay, which he titled “Slavery in Massachusetts.” Within a year of his return to Richmond, Burns was purchased by funds raised by a black church in Boston and he achieved freedom.

Sourcing Questions

- Who was the audience of Thoreau’s speech?

- Who was the audience of Thoreau’s essay?

- Why would Thoreau have found it important to share his sentiments regarding slavery with a larger audience?

| Vocabulary | Text |

|---|---|

| Much has been said about American slavery, but I think that we do not even yet realize what slavery is. If I were seriously to propose to Congress to make mankind into sausages, I have no doubt that most of the members would smile at my proposition, and if any believed me to be in earnest, they would think that I proposed something much worse than Congress had ever done. But if any of them will tell me that to make a man into a sausage would be much worse- would be any worse- than to make him into a slave- than it was to enact the Fugitive Slave Law- I will accuse him of foolishness, of intellectual incapacity, of making a distinction without a difference. The one is just as sensible a proposition as the other. . . . | |

| pernicious (adj): evil | I believe that in this country the press exerts a greater and a more pernicious influence than the church did in its worst period. We are not a religious people, but we are a nation of politicians. We do not care for the Bible, but we do care for the newspaper. At any meeting of politicians- like that at Concord the other evening, for instance- how impertinent it would be to quote from the Bible! how pertinent to quote from a newspaper or from the Constitution! The newspaper is a Bible which we read every morning and every afternoon, standing and sitting, riding and walking. It is a Bible which every man carries in his pocket, which lies on every table and counter, and which the mail, and thousands of missionaries, are continually dispersing. It is, in short, the only book which America has printed and which America reads. So wide is its influence. The editor is a preacher whom you voluntarily support. Your tax is commonly one cent daily, and it costs nothing for pew hire. . . . |

| preeminently (adv): primarily | Covered with disgrace, the State has sat down coolly to try for their lives and liberties the men who attempted to do its duty for it. And this is called justice! They who have shown that they can behave particularly well may perchance be put under bonds for their good behavior. They whom truth requires at present to plead guilty are, of all the inhabitants of the State, preeminently innocent. While the Governor, and the Mayor, and countless officers of the Commonwealth are at large, the champions of liberty are imprisoned. |

| Only they are guiltless who commit the crime of contempt of such a court. It behooves every man to see that his influence is on the side of justice, and let the courts make their own characters. My sympathies in this case are wholly with the accused, and wholly against their accusers and judges. Justice is sweet and musical; but injustice is harsh and discordant. The judge still sits grinding at his organ, but it yields no music, and we hear only the sound of the handle. He believes that all the music resides in the handle, and the crowd toss him their coppers the same as before. |

Comprehension Questions

- How does Thoreau use an absurd hypothetical scenario to prove his point about the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850?

- Why does Thoreau compare the newspaper with the Bible, and how does this comparison tie in to his argument about slavery?

- What is Thoreau’s opinion of the judicial system in Massachusetts?

- Why does Thoreau compare the judge to an organ grinder?

Historical Reasoning Questions

- As a transcendentalist writer, Thoreau argued that human beings are innately good, that they must use subjective intuition to make sense of the world, and that immersion in and respect for the natural environment is of tremendous importance. In what excerpts from this essay does Thoreau draw on the transcendentalist philosophy to protest the institution of slavery?

- How does Thoreau use metaphors to illustrate his argument against slavery and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850?

Selections from “Slavery in Massachusetts” by Henry David Thoreau, 1854 http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Slavery_Massachusetts.html