Challenges of American Citizenship in the new Millennium

There is no way the Constitution will work if the people lose their virtue. Almost every Founding Father said or wrote something along these lines. A self-governing polity can only succeed when it is composed of individuals who can govern themselves. And if the people do not control themselves, they will either descend into self-destructive anarchy or come together in support of a dictator or despot emerging to embody their collective greed and lust for power. They would vote to give him more and more power, even as they congratulated themselves on their wisdom.

George Washington and Virtue

When George Washington was unanimously elected to serve as the first president of the United States, he made a connection between virtue and liberty.

As he said in his First Inaugural Address, “there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness… the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained” (George Washington, “First Inaugural Address,” April 30, 1789).

This connection between virtue and happiness was one of these “eternal rules of order and right.” It could not be wished away or ignored. The virtue of individual people would amount to the virtue of the nation.

Washington concluded that “the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered, perhaps, as deeply, as finally, staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people” (Washington, “First Inaugural Address”).

It was the responsibility of the American people to be virtuous and preserve the self-government they had created.

As a general in the War for Independence, Washington had displayed courage and fortitude; as the nation’s first president, he demonstrated prudence and future-mindedness in his work to keep the United States out of the war between France and England during his second term. When Washington refused to run for a third term as president—thus establishing a two-term limit that would last until the mid-twentieth century—he provided an example of prudent moderation to the American people by voluntarily yielding his power.

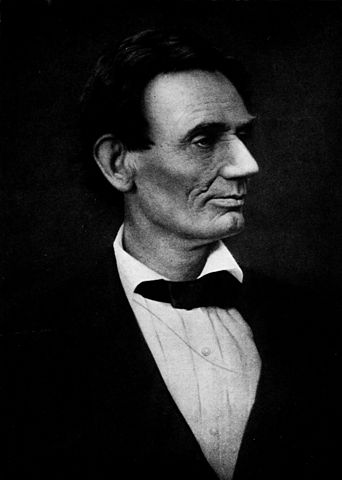

Abraham Lincoln and Virtue

Times change, but the need for virtue remains. Abraham Lincoln gave his Second Inaugural Address in 1865, four years into the Civil War. He urged the American people to remember the importance of virtue. By ignoring the virtues of charity and justice, Americans both North and South had allowed a terrible evil to endure: slavery.

He spoke of the country divided, yet equally deserving of God’s justice: “Both [northerners and southerners] read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.” The war, he said, must be God’s punishment for the sin of slavery: “He [God] gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came.” Referring to the virtues of citizenship that he believed were especially needed, Lincoln called on Americans to act “with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations” (Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1865).

Lincoln was assassinated a month later by a southern sympathizer.

John F. Kennedy and Virtue

One hundred years after the start of the Civil War, President John F. Kennedy took the oath of office and delivered his inaugural address. Recalling Washington and his time, Kennedy reminded citizens that “we are the heirs of that first revolution.” He called upon Americans to take responsibility for protecting freedom:

“And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country…Whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own” (John F. Kennedy, “Inaugural Address,” January 20, 1961).

Kennedy stressed, in other words, the virtues of individual responsibility and sacrifice.

Modern Challenges of Citizenship

Washington was president more than 200 years ago. Lincoln, 150 years ago. And Kennedy, 50. Are the virtues they championed—moderation, charity, justice, responsibility, and sacrifice—irrelevant now that so many years have gone by and times have so much changed? Americans look to their leaders, especially presidents, to set an example of virtue and praise acting virtuously.

Aristotle defined virtues such as moderation, justice, courage, and generosity. People have embraced and strived to live out the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love for hundreds and thousands of years. The same goes for the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude. Ben Franklin identified as virtues for good living the qualities of industry, frugality, and temperance.

In the eighteenth century in particular, virtue was understood to be a masculine quality (the Latin root of virtue is vir, which means “man”) that embraced self-sufficiency, independence of mind and means, and the abilities to provide for oneself and one’s family.

The Founders imagined farmers to be especially virtuous because their ownership of land and habits of hard work meant that they could do all these things. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and many other Founders embodied this gentleman farmer ideal. They were their own bosses and regarded each other with a recognition of rough moral, social, and politically equality that was well-suited for life in a free republic. Not only that, but these farmers were almost literally rooted in the soil; they were permanent residents of their communities and thus had an interest in doing well by their neighbors and contributing voluntarily to the common good.

While some people argue that circumstances determine what is good and what is bad, the classic virtues of America’s founding maintain that justice (for example) is good in any situation. Industry is good, no matter what the circumstances. It is never wrong to be courageous, honest, prudent, and selfless. In other words, times change, but virtue does not.

If it’s true that virtues do not change, then the ones we need in our own time cannot be different from the ones needed by the citizens who lived in the days of Aristotle, Franklin, Washington, Lincoln, or Kennedy. We may apply them in different ways—we may need to show courage against enemies in a different form, or practice industry in different settings, or work for justice in different contexts—but the virtues remain. As Washington said, our American experiment in liberty depends on our living them out.